Gratitude to Robert Sams for the creation of Seignorage Shares and perspectives on how to accurately assess fluctuating coins in multi-currency frameworks

Note: we do not intend to incorporate price stabilization into ether; our approach has always been to keep ether straightforward to mitigate black-swan risks. Findings from this study will likely contribute to either subcurrencies or standalone blockchains

A primary issue with Bitcoin for average users is that, although the network may serve as an excellent method for transferring payments, offering reduced transaction fees, a far-reaching global presence, and a significant degree of censorship resistance, Bitcoin as a currency is an extremely unstable means of preserving value. Despite the currency’s considerable growth over the previous six years, particularly within financial markets, past performance does not provide assurance (and according to the efficient market hypothesis, not even an indication) of future anticipated value results, and the currency has a notorious record for severe volatility; over the past eleven months, Bitcoin holders have witnessed a decline of approximately 67% in their wealth, and frequently the price fluctuates by up to 25% within just one week. In light of this concern, there is increasing curiosity about a straightforward question: is it possible to achieve the best of both worlds? Can we attain the complete decentralization that a cryptographic payment network provides while simultaneously enjoying a higher degree of price stability, avoiding such dramatic fluctuations?

Last week, a group of Japanese researchers put forth a proposal for an “enhanced Bitcoin”, which sought to do precisely that: while Bitcoin possesses a fixed supply and a fluctuating price, the researchers’ Enhanced Bitcoin would adjust its supply in efforts to alleviate price shocks. Nevertheless, the challenge of developing a price-stable cryptocurrency, as the researchers recognized, differs significantly from merely establishing an inflation target for a central bank. The fundamental issue is more complex: how can we aim for a fixed price in a manner that is both decentralized and resilient against attacks?

To address the problem accurately, it is advantageous to dissect it into two primarily distinct sub-problems:

- How can we assess a currency’s price in a decentralized manner?

- Given a desired supply adjustment to target the price, to whom do we distribute and how do we absorb currency units?

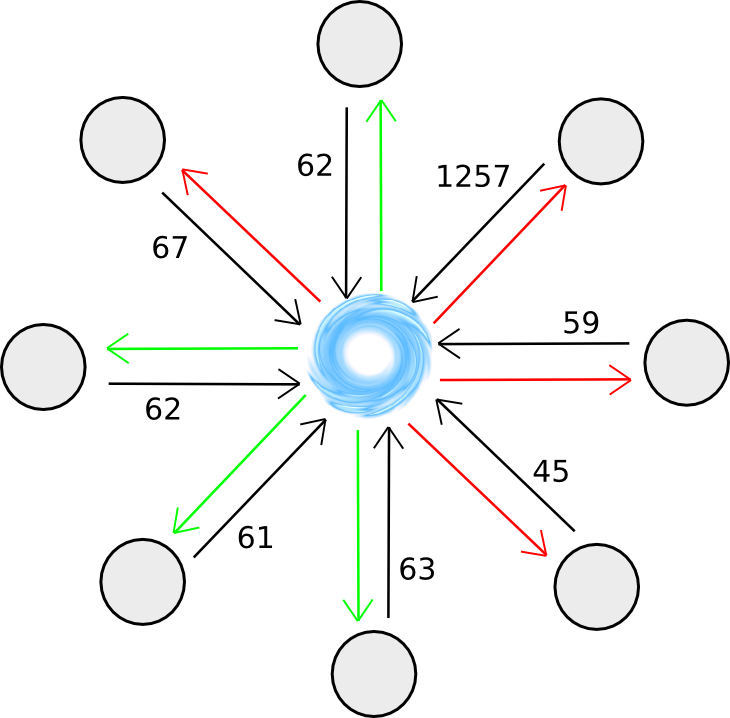

Decentralized Measurement

In terms of the decentralized measurement challenge, there are two primary recognized categories of solutions: exogenous solutions, mechanisms that aim to evaluate the price concerning a specific external index, and endogenous solutions, mechanisms that seek to utilize internal factors of the network to gauge price. Regarding exogenous solutions, thus far the only reliably known category of mechanisms for (potentially) cryptoeconomically securely assessing the importance of an exogenous variable are the various forms of Schellingcoin – fundamentally, gathering votes from everyone to determine the outcome (using a selection method randomly derived based on mining power or currency stake to avert sybil attacks), rewarding all who provide results that closely match the majority consensus. If you presume that others will offer accurate information, then it is in your best interest to present accurate information to align with the consensus – an inherently reinforcing mechanism quite similar to cryptocurrency consensus itself.

The significant drawback of Schellingcoin is the ambiguity surrounding the stability of the consensus. Specifically, what if a moderately sized participant announces an alternative value that could be advantageous for most participants to accept, and somehow they manage to coordinate a switch? If a substantial incentive exists, and the user pool is relatively centralized, it might not be overly challenging to organize such a switch.

Three primary elements can influence the degree of this vulnerability:

- Is it probable that the individuals involved in a Schellingcoin have a shared incentive to skew the outcome in a particular direction?

- Do the participants hold a common stake in the system which could be diminished if the system were to be dishonest?

- Is it feasible to “credibly commit” to a specific response (i.e., commit to presenting the response in a manner that can’t easily be altered)?

(1) poses considerable challenges for single-currency frameworks, as if the participant group is selected based on their stake in the currency, they have a substantial incentive to feign a lower currency price, so the compensation mechanism pushes it upwards. Conversely, if the participant group is determined by mining power, there is a significant motive to falsely represent the currency’s price as inflated to boost issuance. However, if there exist two types of mining, one used for choosing Schellingcoin participants and the other for obtaining a variable reward, then this concern becomes irrelevant, permitting multi-currency systems to circumvent the issue. (2) holds true if participant selection relies on either stake (preferably, long-term bonded stake) or ASIC mining, yet is inaccurate for CPU mining. Nonetheless, we shouldn’t solely depend on this incentive to outweigh (1).

(3) might be the most challenging; it hinges upon the specific technical execution of the Schellingcoin. A straightforward implementation of merely submitting the values to the blockchain presents difficulties because an early submission of one’s value constitutes a credible commitment. The initial SchellingCoin utilized a mechanism where everyone submitted a hash of their value in the first round, followed by the actual value in the second round, resembling a cryptographic equivalent where everyone places down a card face down first and then reveals them simultaneously; however, this method also permits credible commitment through early revelation (even if not submission) of one’s value, as the value can be verified against the hash.

A third alternative entails requiring all participants to directly submit their values, but only during a specific block; should a participant reveal a submission prematurely, they can always “double-spend” it. The 12-second block time ensures minimal opportunity for coordination. The creator of the block can be strongly incentivized (or even, if the Schellingcoin represents an independent blockchain, mandated) to integrate all submissions, thereby discouraging or preventing the block maker from selectively including answers. A fourth category of options consists of some

secret sharing or secure multiparty computation mechanism, employing a network of nodes, themselves chosen by stake (potentially even the participants themselves), as a kind of decentralized alternative for a centralized server solution, along with all the confidentiality that such a method encompasses.

Lastly, a fifth tactic is to conduct the schellingcoin “blockchain-style”: each interval, a random stakeholder is chosen, and instructed to deliver their vote in the form of a [id, value] pair, where value represents the legitimate valid and id signifies an identifier of the preceding vote that appears correct. The motivation to vote accurately is that only tests that persist in the primary chain after a certain number of blocks are rewarded, and upcoming voters will avoid attaching their vote to a vote that is inaccurate, fearing that if they do, subsequent voters will dismiss their vote.

Schellingcoin remains an unproven experiment, and thus there is valid justification to be doubtful regarding its effectiveness; however, if we aspire to achieve anything resembling an ideal price measurement system, it is currently the sole mechanism available. If Schellingcoin is found to be impractical, we will have to rely on alternative strategies: the endogenous ones.

Endogenous Solutions

To ascertain the price of a currency endogenously, what we fundamentally need is to identify some service within the network that is acknowledged to have a relatively stable real-value price, and evaluate the cost of that service within the network as expressed in the network’s own token. Illustrations of such services comprise:

- Computation (assessed via mining difficulty)

- Transaction fees

- Data storage

- Bandwidth provision

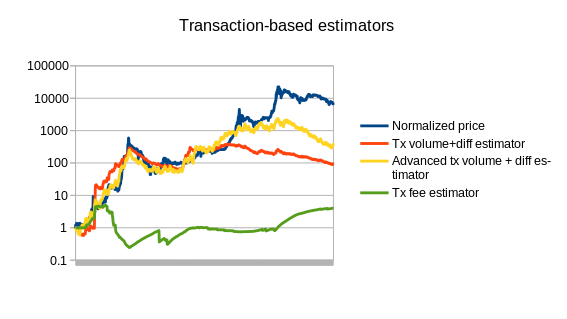

A slightly alternate, yet related, strategy is to quantify a statistic that correlates indirectly with price, typically a metric of the extent of utilization; one example of this is transaction volume.

The issue with all of these services, however, is that none of them are particularly resilient to swift changes caused by technological advancement. Moore’s Law has thus far assured that most kinds of computational services decrease in cost at a rate of 2x every two years, and it could easily accelerate to 2x every 18 months or 2x every five years. Therefore, attempting to tie a currency to any of those variables will likely result in a system that is hyperinflationary, necessitating more advanced strategies for utilizing these variables to ascertain a more stable metric of price.

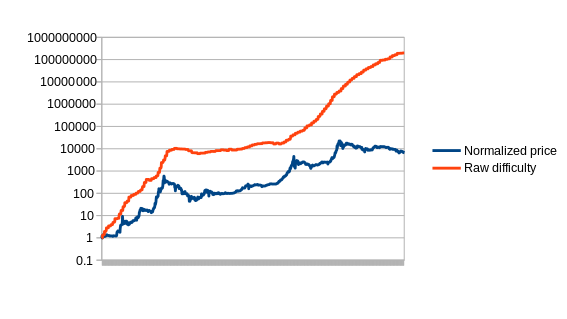

First, let us define the problem. Formally, we characterize an estimator as a function that receives a data stream of some input variable (e.g., mining difficulty, transaction expenses in currency units, etc) D[1], D[2], D[3]…, and must emit a stream of estimates of the currency’s price, P[1], P[2], P[3]… The estimator clearly cannot predict the future; P[i] can depend on D[1], D[2] … D[i], but not D[i+1]. Now, to initiate, let us plot the simplest conceivable estimator based on Bitcoin, which we will designate as the naive estimator: difficulty equals price.

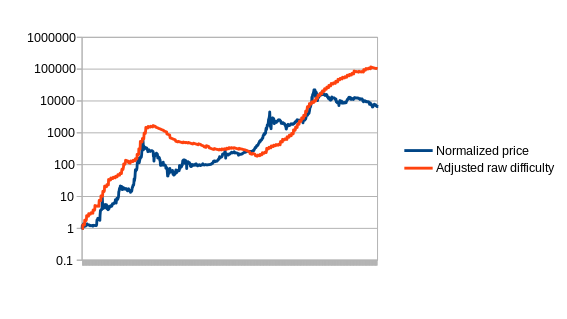

Regrettably, the flaw of this approach is apparent from the graph and was previously mentioned: difficulty is a function of both price and Moore’s law, resulting in outcomes that diverge from any precise measure of the price exponentially over time. The first immediate tactic to remedy this issue is to attempt to offset Moore’s law by utilizing the difficulty but artificially diminishing the price by a fixed amount each day to counterbalance the anticipated pace of technological enhancement; we shall refer to this as the compensated naive estimator. Note that an infinite number of variations of this estimator exist, one for each rate of depreciation, and all of the other estimators presented here will also include parameters.

The method we will employ to select the parameter for our variant is by utilizing a form of simulated annealing to identify the optimal values, employing the first 780 days of Bitcoin pricing as “training data”. The estimators are then evaluated according to how they would perform over the remaining 780 days, to observe their reactions to conditions that were unknown when the parameters were adjusted (this method, known as “cross-validation”, is standard in the fields of machine learning and optimization theory). The optimal value for the compensated estimator results in a decrease of 0.48% daily, yielding this chart:

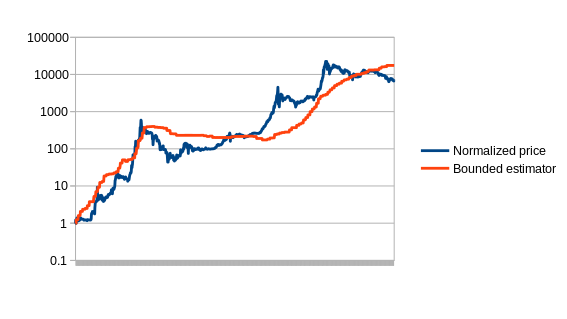

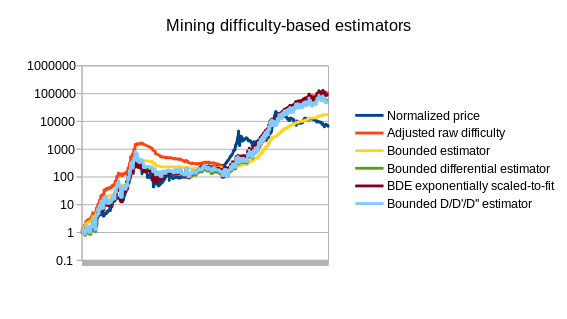

The next estimator we will investigate is the bounded estimator. The functioning of the bounded estimator is somewhat more intricate. By default, it presumes that all increases in difficulty are attributed to Moore’s law. However, it assumes that Moore’s law cannot regress (i.e., technology deteriorating), and that Moore’s law cannot accelerate beyond a certain rate – in our case, 5.88% per fortnight, or approximately quadrupling annually. Any growth beyond these limits is assumed to originate from price increases or decreases. Therefore, for instance, if the difficulty climbs by 20% during one period, it assumes that 5.88% of this is due to technological improvements, while the remaining 14.12% results from a price surge, and thus a stabilizing currency based on this estimator might raise supply by 14.12% to compensate. The theory is that cryptocurrency price growth largely occurs in rapid bubbles, and hence the bounded estimator should be capable of capturing the majority of the price escalation during such occurrences.

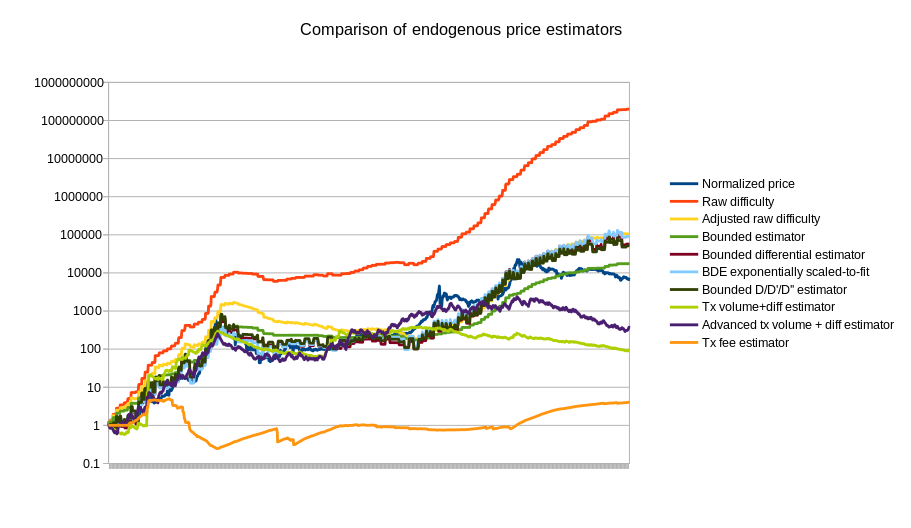

There are additionally more sophisticated strategies; the optimal strategies should consider the fact that ASIC farms require time to establish, and also adhere to a hysteresis phenomenon: it’s frequently feasible to maintain an ASIC farm operational if you already possess it, even when under identical conditions it would not be feasible to initiate a new one. An uncomplicated method is assessing the rate of growth in difficulty, not merely the difficulty itself, or even employing a linear regression analysis to forecast difficulty 90 days into the future. Below is a graph featuring the aforementioned estimators, along with a few additional ones, juxtaposed with the actual price:

Be aware that the graph also showcases three estimators that utilize metrics besides Bitcoin mining: both a basic and an advanced estimator using transaction volume, alongside an estimator that takes the average transaction fee into account. We can also differentiate the mining-related estimators from the alternative estimators:

|

|

Refer to https://github.com/ethereum/economic-modeling/tree/master/stability for the source code that generated these findings.

Naturally, this is merely the commencement of endogenous price estimator theory; a more extensive analysis encompassing dozens of cryptocurrencies will probably extend much further. The most effective estimators may ultimately utilize a blend of various metrics; considering how the difficulty-based estimators exceeded the price in 2014 while the transaction-based estimators fell short, a combination of the two could prove to be significantly more precise. Additionally, the challenge is expected to diminish over time as the Bitcoin mining ecosystem stabilizes toward something resembling an equilibrium, where technological advancements occur only as swiftly as the conventional Moore’s law, which suggests a doubling of capabilities every 2 years.

To understand the potential of these estimators, we can observe from the charts that they may mitigate at least 50% of cryptocurrency price fluctuations and could rise to approximately 67% once the mining sector stabilizes. Something akin to Bitcoin, if it achieves mainstream adoption, will likely exhibit somewhat greater instability than gold, but not excessively unstable – the primary difference between BTC and gold is that the supply of gold can indeed increase as the price escalates, since more can be mined if miners are willing to incur higher costs, implying an inherent dampening effect; however, the supply elasticity of gold is surprisingly not that substantial; production saw minimal increases during the price surges of the 1970s and 2000s. Gold prices remained within a spectrum of 4.63x ($412 to $1980) over the last decade; logarithmically diminishing that by two thirds results in a range of 1.54x, not substantially exceeding EUR/USD (1.37x), JPY/USD (1.64x) or CAD/USD (1.41x); consequently, endogenous stabilization could indeed be quite feasible and may be favored for its independence from any particular centralized currency or governing body.

Another challenge that all of these estimators face is susceptibility to exploitation: if transaction volume is leveraged to ascertain the currency’s price, then an adversary can easily influence the price by simply generating numerous transactions. The average transaction fees for Bitcoin hover around $5000 daily; at that price in a stabilized currency, an attacker could feasibly halve the price. However, mining difficulty is considerably more challenging to manipulate due to the extensive market size. If a platform opts not to embrace the inefficiencies of wasteful proof of work, an alternative could involve establishing a market for other resources, such as storage; Filecoin and Permacoin are projects that endeavor to utilize a decentralized file storage market as a consensus mechanism, and this same market could effortlessly serve as a dual-purpose estimator.

The Issuance Problem

Now, even if we possess a fairly reliable, or potentially flawless, estimator for the currency’s price, we still face the second dilemma: how do we distribute or absorb currency units? The most straightforward method is to simply distribute them as a mining reward, as suggested by Japanese researchers. However, this presents two main issues:

- Such a mechanism can solely issue new currency units when the price is excessively high; it cannot absorb currency units when the price is significantly low.

- If mining difficulty is employed in an endogenous estimator, then the estimator must consider that some increases in mining difficulty will be a consequence of an elevated issuance rate triggered by the estimator itself.

If not approached with utmost caution, the second challenge holds the potential to create perilous feedback loops in either direction; however, if we utilize an alternate market as both an estimator and an issuance model, this problem can be circumvented. The first issue does indeed appear serious; in fact, one can interpret this as indicating that any currency utilizing this model will consistently be less favorable than Bitcoin, since Bitcoin will eventually reach an issuance rate of zero, while a currency employing this mechanism will consistently maintain an issuance rate above zero. Therefore, such a currency will always be more inflationary, rendering it less appealing to retain. Nevertheless, this assertion is not entirely accurate; the reasoning is that when a user acquires units of the stabilized currency, they possess greater assurance that at the moment of acquisition the units are not already overvalued and hence will not depreciate soon. Alternatively,one can observe that exceptionally large fluctuations in value are warranted by shifting assessments of the likelihood that the currency will become exponentially more costly; removing this possibility will lessen the upward and downward range of these fluctuations. For individuals who prioritize stability, this risk mitigation may indeed surpass the general rise in long-term supply inflation.

BitAssets

An alternate method is the (initial version of the) “bitassets” tactic employed by Bitshares. This method can be outlined as follows:

- Two currencies exist, “vol-coins” and “stable-coins”.

- Stable-coins are perceived to maintain a value of $1.

- Vol-coins represent a tangible currency; users can hold either a zero or positive balance of them. Stable-coins only exist in the form of contracts-for-difference (for instance, each negative stable-coin is essentially a liability to another party, secured by at least double the value in vol-coins, and each positive stable-coin signifies the ownership of that liability).

- Should an individual’s stable-coin liability surpass 90% of the value of their vol-coin collateral, the liability is nullified, and the entire vol-coin collateral is transferred to the counterpart (“margin call”).

- Users may freely exchange vol-coins and stable-coins with one another.

And that sums it up. The critical element that (allegedly) enables the mechanism to function is the idea of a “market peg”: as everyone acknowledges that stable-coins are intended to be worth $1, if the value of a stable-coin drops below $1, then it will lead people to believe it will eventually revert back to $1, prompting them to purchase it, thereby ensuring it indeed returns to $1 – a self-fulfilling prophecy premise. Similarly, if the price rises above $1, it is expected to decrease back down. Because stable-coins represent a zero-total-supply currency (i.e., each positive unit corresponds to a related negative unit), the mechanism is not fundamentally unfeasible; a price of $1 could remain stable with ten participants or ten billion participants (remember, fridges count as users too!).

Nevertheless, the mechanism possesses notable fragility traits. Certainly, if a stable-coin drops to $0.95, and it’s a minor decline that can be easily rectified, then the mechanism will activate, and the price will swiftly rebound to $1. However, if it hastily plunges to $0.90, or lower, users may interpret this decrease as an indication that the peg is genuinely breaking, prompting them to rush to exit while they still can – causing the price to decline even further. Ultimately, the stable-coin could very well end up losing all value. In the real world, markets frequently exhibit positive feedback loops, and it seems quite probable that the sole reason the system hasn’t unraveled yet is due to the existence of a large centralized entity (BitShares Inc) that is prepared to serve as a last-resort buyer to sustain the “market” peg if required.

It should be noted that BitShares has transitioned to a somewhat different model involving price feeds furnished by the delegates (participants in the consensus algorithm) of the system; thus, the risks of fragility are likely considerably reduced now.

SchellingDollar

A method that bears a loose resemblance to BitAssets but arguably performs much better is the SchellingDollar (named as such since it was originally designed to function with the SchellingCoin price detection mechanism, though it can also utilize endogenous estimators), defined as follows:

- Two currencies exist, “vol-coins” and “stable-coins”. Vol-coins are initially distributed through some method (e.g., pre-sale), but at the outset, no stable-coins are available.

- Users may possess only a zero or positive balance of vol-coins. Users can have a negative balance of stable-coins, but they may only obtain or increase their negative balance of stable-coins if they have a quantity of vol-coins equivalent in value to twice their new stable-coin balance (e.g., if a stable-coin is $1 and a vol-coin is $5, then if a user has 10 vol-coins ($50), they can at most reduce their stable-coin balance to -25).

- If the value of a user’s negative stable-coins exceeds 90% of the value of their vol-coins, the user’s stable-coin and vol-coin balances are consequently reduced to zero (“margin call”). This prevents scenarios where accounts feature negative-valued balances and the system faces bankruptcy as users flee from their liabilities.

- Users can convert their stable-coins into vol-coins or vice versa at a rate of $1 worth of vol-coin per stable-coin, possibly with a 0.1% conversion fee. This mechanism is, of course, subject to the constraints described in (2).

- The system tracks the total volume of stable-coins in circulation. If the quantity exceeds zero, it applies a negative interest rate to make positive stable-coin holdings less desirable and negative holdings more appealing. If the quantity is below zero, the system similarly enacts a positive interest rate. Interest rates can be fine-tuned via something akin to a PID controller, or even a straightforward “increase or decrease by 0.2% daily based on whether the quantity is positive or negative” system.

In this instance, we do not merely presume that the market will maintain the price at $1; rather, we employ a central-bank-style interest rate targeting system to artificially discourage the holding of stable-coin units if the supply is overly abundant (i.e., greater than zero), and encourage the holding of stable-coin units if the supply is too scarce (i.e., less than zero). Be aware that fragility risks remain present. Firstly, if the vol-coin price declines by more than 50% rapidly, many margin call scenarios will be activated, sharply shifting the stable-coin supply to the positive side, thus enforcing a high negative interest rate on stable-coins. Secondly, if the vol-coin market is too illiquid, it becomes susceptible to manipulation, allowing attackers to instigate margin call cascades.

Another point of concern is, what makes vol-coins valuable? Scarcity alone will not confer substantial value, as vol-coins are inferior to stable-coins for transactional purposes. The answer can be observed by modeling the system as a form of decentralized corporation, where “achieving profits” equates to accumulating vol-coins and “incurring losses” relates to issuing vol-coins. The profit and loss scenarios of the system are outlined as follows:

- Gain: transaction charges from swapping stable-coins for vol-coins

- Gain: the additional 10% in margin call scenarios

- Deficit: occurrences where the vol-coin value decreases while the aggregate stable-coin supply is positive, or increases while the total stable-coin supply is negative (the first scenario is more likely to occur, due to margin-call circumstances)

- Gain: situations where the vol-coin value increases while the overall stable-coin supply is positive, or decreases while it’s negative

It is important to note that the second gain is, in some respects, a fictitious profit; when users possess vol-coins, they need to factor in the likelihood of being impacted by this extra 10% charge, nullifying the benefit to the system from the existing profit. Nevertheless, one could contend that due to the Dunning-Kruger effect, users may underestimate their vulnerability to incurring a loss, and thus the compensation will be under 100%.

Now, let’s think about a tactic where a user attempts to maintain a consistent share of all vol-coins. When x% of vol-coins are acquired, the user liquidates x% of their vol-coins to realize a gain, and when new vol-coins equivalent to x% of the current supply are issued, the user boosts their holdings by that same fraction, suffering a loss. Therefore, the user’s overall gain is proportional to the cumulative profit of the system.

Seignorage Shares

A fourth model is termed “seignorage shares”, courtesy of Robert Sams. Seignorage shares is a rather sophisticated system that, in my simplified interpretation, functions as follows:

- There are two currencies, “vol-coins” and “stable-coins” (Sams refers to them as “shares” and “coins”, respectively)

- Anyone can buy vol-coins with stable-coins or vice versa from the system at a price of $1 worth of vol-coin for each stable-coin, possibly incurring a 0.1% exchange fee

Note that in Sams’ approach, auctions were utilized to sell newly generated stable-coins should the price rise excessively and to purchase if it fell too low; this mechanism effectively serves the same purpose, substituting a constant fixed price for an auction. Nevertheless, this simplicity does result in some level of fragility. To understand why, let’s conduct a similar valuation assessment for vol-coins. The profit and loss scenarios are straightforward:

- Gain: acquiring vol-coins to issue new stable-coins

- Deficit: issuing vol-coins to acquire stable-coins

The same valuation approach applies as in the previous case, allowing us to see that the value of the vol-coins correlates to the anticipated total future rise in the supply of stable-coins, modified by some discount factor. Thus, herein lies the challenge: if the system is perceived by all participants as “winding down” (for example, users are leaving it for a superior alternative), leading to the expectation that the total stable-coin supply will diminish permanently, then the value of the vol-coins may plummet below zero, causing vol-coins to hyperinflate, which in turn leads to stable-coins hyperinflating as well. Conversely, in exchange for this fragility risk, vol-coins can attain significantly higher valuations, making the scheme considerably more appealing to crypto-platform developers aiming to generate revenue via token sales.

It’s worth noting that both the SchellingDollar and seignorage shares, when operating on independent networks, must also consider transaction fees and consensus expenses. Luckily, with proof of stake, consensus should be achievable at a lower cost than transaction fees, allowing for the difference to be added to profits. This potentially expands the market cap for the SchellingDollar’s vol-coin and ensures the market cap of seignorage shares’ vol-coins stays above zero even if there is a significant, albeit not total, permanent reduction in stable-coin volume. Ultimately, however, there exists an unavoidable degree of fragility: at a minimum, if interest in a system wanes to nearly zero, the system can be subject to double-spending, and estimators and Schellingcoins become overly exploited. Even sidechains, as a method for preserving a single currency across multiple networks, are vulnerable to this issue. The critical queries are simply (1) how do we mitigate the risks, and (2) given that risks are present, how do we convey the system to users such that they do not become excessively reliant on something that could fail?

Conclusions

Are stable-value assets essential? Considering the significant interest in “blockchain technology” juxtaposed with the disinterest in “Bitcoin the currency” observed among many in the mainstream, perhaps it is the right moment for stable-currency or multi-currency systems to emerge. This scenario could lead to various distinct types of crypto-assets: stable assets designated for trading, speculative assets allocated for investment, and Bitcoin itself may ultimately function as a unique Schelling point for a universal fallback asset, reminiscent of gold’s historical role.

If this were to materialize, especially if a more robust version of price stability grounded in Schellingcoin strategies could take hold, the cryptocurrency landscape might find itself in a fascinating predicament: there could be thousands of cryptocurrencies, many of which would be volatile, while numerous others would be stable-coins, all adjusting prices almost in sync with one another; thus, this situation might be represented in interfaces as one super-currency, with different blockchains randomly offering positive or negative interest rates, akin to Ferdinando Ametrano’s “Hayek Money”. The genuine cryptoeconomy of the future may not even have started to take shape.