The main financial obligation that a blockchain must cover is its security. The blockchain needs to compensate miners or validators to participate monetarily in its consensus mechanism, whether proof of work or proof of stake, and this inevitably results in some expense. There are two methods to finance this expenditure: inflation and transaction fees. Presently, Bitcoin and Ethereum, the two foremost proof-of-work blockchains, both rely heavily on inflation to secure their networks; the Bitcoin community currently plans to gradually reduce the inflation rate and ultimately transition to a transaction-fee-only model. NXT, one of the more prominent proof-of-stake blockchains, finances its security entirely through transaction fees, and in fact, it experiences negative net inflation since certain on-chain functionalities necessitate the destruction of NXT; the circulating supply is 0.1% lower than the original 1 billion. The question arises: how much “defense spending” is essential for a blockchain to maintain its security, and given a specific amount of necessary spending, what is the most effective way to obtain it?

Absolute Size of PoW / PoS Rewards

To provide some empirical information for the upcoming section, let’s examine bitcoin as a case study. Over recent years, bitcoin transaction revenues have fluctuated between 15-75 BTC daily, which equates to approximately 0.35 BTC for each block (or 1.4% of the current mining rewards), and this has remained constant despite significant variations in adoption levels.

It becomes quite evident why this is true: surges in BTC adoption will raise the total amount of USD-denominated fees (whether through increases in transaction volume, higher average fees, or a mix of both) while simultaneously reducing the amount of BTC available for a specific quantity of USD. Therefore, it is entirely reasonable that, barring any external block size crises, fluctuations in adoption that do not alter the fundamental market structure will largely leave the BTC-denominated total transaction fee levels unchanged.

In 25 years, bitcoin mining rewards are anticipated to nearly vanish; thus, the 0.35 BTC per block will be the sole source of income. At current prices, this translates to approximately ~$35,000 daily or $10 million annually. We can estimate the expense of amassing sufficient mining power to seize control of the network under these circumstances in several ways.

First, we can examine the network’s hash power and the cost associated with consumer miners. The current network possesses 1,471,723 TH/s of hash power, while the best available miners cost $100 for every 1 TH/s, meaning acquiring enough of these miners to overpower the existing network would cost about ~$147 million USD. If we disregard mining rewards, revenues will decrease by a factor of 36; thus, the mining ecosystem will in the long run shrink by the same factor, making the cost $4.08 million USD. Note that this applies if you are purchasing new miners; if you opt to buy existing miners, you only need to acquire half of the network, thereby reducing what Tim Swanson refers to as a “Maginot line” attack to approximately ~$2.04 million USD.

However, professional mining facilities are likely able to procure miners at significantly lower prices than consumer prices. We can refer to the available information on Bitfury’s $100 million data center, which is projected to consume 100 MW of electricity. This facility will feature a combination of 28nm and 16nm chips; the 16nm chips “achieve energy efficiency of 0.06 joules per gigahash”. Since we are interested in calculating the cost for a new attacker, we will assume that an attacker replicating Bitfury’s accomplishment will exclusively utilize 16nm chips. 100 MW at 0.06 joules per gigahash (a physics reminder: 1 joule per GH = 1 watt per GH/sec) equals 1.67 billion GH/s, or 1.67M TH/s. Consequently, Bitfury managed to operate at $60 per TH/s, yielding a cost of $2.45 million for an external attack and $1.22 million for acquiring existing miners.

Thus, we have an approximate estimate of $1.2-4 million for a “Maginot line attack” against a fee-only network. Cheaper assaults (for instance, “renting” hardware) could cost 10-100 times less. Should the bitcoin ecosystem expand, this figure will naturally rise, but the transaction sizes conducted over the network will also increase, thus raising the motivation for an attack as well. Is this level of security sufficient to protect the blockchain from attacks? It remains unclear; it is my personal belief that the risk is quite high that this may be inadequate and therefore, it is precarious for a blockchain protocol to commit to this level of security without a mechanism for enhancing it (keep in mind that Ethereum’s current proof of work does not present any fundamental improvements over Bitcoin’s in this aspect; this is the reason why I have been hesitant to agree to an ether supply cap at this juncture).

In a proof of stake scenario, security is likely to be significantly greater. To understand why, consider the ratio between the calculated cost of taking control of the bitcoin network and the annual mining revenue ($932 million at present BTC price levels); this ratio is exceedingly low: the capital expenses are only about two months’ worth of revenue. In a proof of stake environment, the cost of deposits should equate to the infinite future discounted total of the returns; that is, assuming a risk-adjusted discount rate of, for example, 5%, the capital costs correspond to 20 years of revenue. It’s noteworthy that if ASIC miners incurred no electricity costs and lasted indefinitely, the equilibrium in proof of work would be identical (except that proof of work would still be more “wasteful” than proof of stake in an economic context, and recovery from successful attacks would be more challenging); however, due to the reality that electricity and notably hardware depreciation constitute the major part of the costs of ASIC mining, a significant disparity exists. Hence, with proof of stake, we might anticipate an attack cost ranging from $20-100 million for a network of Bitcoin’s size; thus, it appears more probable that the level of security will be adequate, but it remains uncertain.

The Ramsey Problem

Let’s assume that depending solely on current transaction fees is inadequate for securing the network. There are two options to generate additional revenue. One approach is to elevate transaction fees by restricting supply below optimal levels, and the other is to introduce inflation. How do we decide on which approach, or what mixture of both, to implement?

Fortunately, there exists a well-established principle in economics for addressing the issue in a manner that minimizes economic deadweight loss, referred to as Ramsey pricing. Ramsey’s initial scenario was as follows. Suppose that there is a regulated monopoly that is obliged to achievea specific profit goal (potentially to achieve breakeven after covering fixed expenses), and competitive pricing (i.e., where the price of a product matches the marginal cost of producing an additional unit of the product) would not be adequate to satisfy that objective. The Ramsey principle states that markup should be inversely related to the demand elasticity; for example, if a 1% price hike in product A leads to a 2% fall in demand, while a 1% price increase in product B results in a 4% decrease in demand, then the socially optimal action would be to set the markup on product A to be twice that of product B (you may observe that this effectively reduces demand uniformly).

The rationale behind adopting this balanced strategy, rather than solely imposing the entire markup on the most inelastic segment of the demand, is that the negative impact of charging prices above marginal cost increases with the square of the markup. Imagine that producing a certain item costs $20, and you sell it for $21. There are probably a few individuals who value the item somewhere between $20 and $21 (let’s assume an average of $20.5), and it represents a significant loss to society that these individuals cannot purchase the item even though they would benefit more from acquiring it than what the seller would lose from parting with it. Nonetheless, this group is small and the total loss (averaging $0.5) is minor. Now, consider that you charge $30. There will now likely be ten times as many individuals with “reservation prices” between $20 and $30, and their average valuation is roughly around $25; thus, there are tenfold more individuals who experience harm, and the average social loss from each is now $5 instead of $0.5, resulting in the overall social loss being 100 times greater. Due to this superlinear escalation, extracting a little from everyone is less detrimental than taking a substantial amount from a small group.

Note how the “deadweight loss” area is triangular. As you (ideally) remember from mathematics, the area of a triangle is calculated as width * height / 2, meaning that doubling the dimensions quadruples the area.

Regarding Bitcoin, we currently observe that transaction fees are and have consistently hovered around ~50 BTC daily, or ~18000 BTC annually, which constitutes ~0.1% of the coin supply. We can approximate that a 2x fee increase would decrease transaction volume by 20%. In practice, it appears that Bitcoin fees have risen approximately ~2x compared to a year ago and it seems reasonable to assert that transaction volume is currently ~20% diminished in comparison to what it would be without the fee increase (refer to this rough estimate); these approximations are significantly unscientific but they serve as a reasonable initial estimation.

Now, suppose that 0.5% annual inflation would diminish the interest in holding BTC by possibly 10%, but let’s conservatively propose 25%. If at any moment the Bitcoin community decides to enhance security expenditures by approximately 200,000 BTC annually, then based on those projections, and assuming that current transaction fees are optimal before factoring in security expenditure considerations, the ideal scenario would be to increase fees by 2.96x and introduce 0.784% annual inflation. Alternative projections of these measures would yield varying results, but regardless, the optimal levels for both the fee increase and the inflation would be greater than zero. I reference Bitcoin as an example because it is the one scenario where we can actively observe the consequences of rising usage limited by a fixed cap, but identical reasoning applies to Ethereum as well.

Game-Theoretic Attacks

Another point to strengthen the case for inflation is that overly depending on transaction fees opens the door to a vast and complex category of game-theoretic attacks. The underlying reason is straightforward: if you behave in a manner that prevents another block from entering the chain, you can appropriate that block’s transactions. Thus, there is an incentive for a validator not only to assist themselves but also to disadvantage others. This is even more direct than selfish-mining attacks, since in selfish mining you harm a specific validator for the benefit of all other validators, whereas in this scenario, attackers often find opportunities to exclusively benefit themselves.

In proof of work, one straightforward attack could be that if you observe a block with a significant fee, you attempt to mine a sibling block containing the same transactions, and then offer a reward of 1 BTC to the next miner who mines on top of your block, incentivizing subsequent validators to include your block rather than the original. Naturally, the initial miner could respond by increasing the bounty, leading to a bidding war, and miners could also counteract such attacks by voluntarily relinquishing most of the fee to the creator of the next block; the final outcome is difficult to predict and it remains uncertain whether it is anywhere near efficient for the network. Similar attacks are also feasible in proof of stake.

How to allocate fees?

Even with a specific allocation of revenue from inflation and transaction fees, there exists an additional decision regarding how the transaction fees are collected. Although most protocols thus far have adopted a singular approach, there is actually a fair amount of flexibility in this regard. The three main options are:

- Fees are awarded to the validator/miner that created the block

- Fees are distributed equally among the validators

- Fees are eliminated

One could argue that the most noticeable distinction lies between the first and second options; differentiating the second and the third can be viewed as a targeting policy decision, which we will examine separately in a subsequent section. The distinction between the first two options is this: when the validator that generates a block receives the fees, they have an incentive proportional to the fee amount to include as many transactions as feasible. Conversely, if the fees are distributed equally, each validator has a negligible incentive.

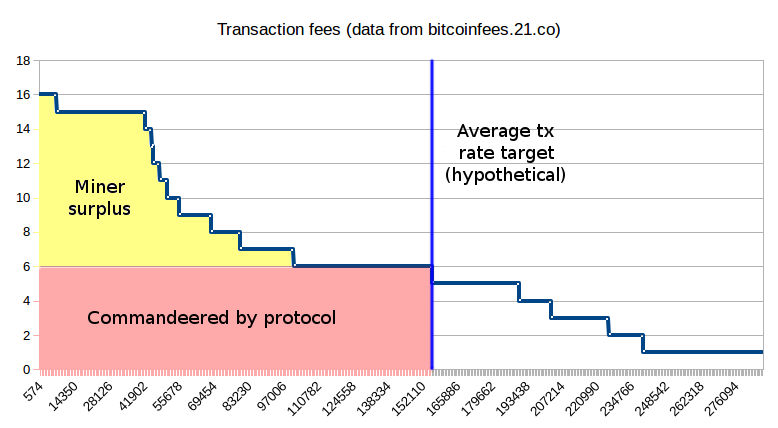

It is important to note that redistributing 100% of fees (or, for that matter, any fixed percentage of fees) is impractical due to “tax evasion” attacks through side-channel payments: instead of adding a transaction fee using the standard mechanism, transaction senders might use a zero or nearly-zero “official fee” and compensate validators directly through other cryptocurrencies (or even PayPal), allowing validators to capture 100% of the revenue. Nevertheless, we can achieve our goals by employing another tactic: establish within the protocol a minimum fee that all transactions must pay, and have the protocol “confiscate” that amount while permitting the miners to retain the entire surplus (alternatively,…miners retain all transaction fees but must consequently pay a fee per byte or unit of gas to the protocol; this is a mathematically equivalent representation). This eradicates tax evasion motivations, while still allocating a significant portion of transaction fee income under the jurisdiction of the protocol, enabling us to maintain fee-based issuance without introducing the game-theoretic adverse incentives of a conventional pure-fee system.

The protocol cannot capture all of the transaction fee proceeds because the fee levels are highly irregular and because it cannot price-discriminate, but it can seize a portion large enough that in-protocol frameworks possess adequate revenue distribution power to address game-theoretic apprehensions associated with traditional fee-only security.

One potential algorithm for establishing this minimum fee could involve an adjustment mechanism similar to difficulty that aims for a medium-term average gas usage equivalent to 1/3 of the protocol gas limit, reducing the minimum fee if average usage falls below this threshold and raising the minimum fee if average usage exceeds it.

We can further expand this framework to introduce other captivating characteristics. One option is a flexible gas limit: instead of a rigid gas limit that blocks cannot surpass, we implement a soft cap G1 and a hard cap G2 (let’s say, G2 = 2 * G1). Assume the protocol fee stands at 20 shannon per gas (in non-Ethereum scenarios, substitute with other cryptocurrency units and “bytes” or alternative block resource limits as appropriate). All transactions up to G1 would incur a fee of 20 shannon per gas. Beyond that threshold, however, fees would escalate: at (G2 + G1) / 2, the marginal unit of gas would cost 40 shannon, at (3 * G2 + G1) / 4 it would escalate to 80 shannon, and so on until reaching a limit of infinity at G2. This would grant the chain a limited capacity to expand to accommodate sudden surges in demand, alleviating price shocks (a feature that some critics of the concept of a “fee market” might appreciate).

What to Target

Suppose we concur with the aforementioned arguments. Then, a question still lingers: how do we aim our policy variables, particularly concerning inflation? Should we aim for a fixed rate of participation in proof of stake (e.g., 30% of all ether), adjusting interest rates accordingly? Should we target a specified total inflation level? Or should we simply set a consistent interest rate, permitting participation and inflation to fluctuate? Or do we pursue a mixed approach where increased interest in participation results in a blend of heightened inflation, increased participation, and a reduced interest rate?

Broadly speaking, trade-offs between targeting rules are essentially trade-offs regarding what types of uncertainty we are more willing to tolerate and which variables we wish to stabilize. The primary motive for targeting a fixed level of participation is to ensure certainty regarding the security level. The key reason for targeting a fixed inflation rate is to fulfill the requirements of some token holders for predictable supply, while simultaneously maintaining a weaker but still present assurance regarding security (theoretically, it is conceivable that only 5% of ether would be participating in equilibrium, but in such a scenario, it would receive a high interest rate, establishing a partial counter-pressure). The main rationale for targeting a fixed interest rate is to minimize selfish-validation threats, as there would be no opportunity for a validator to gain personally by harming the interests of fellow validators. A hybrid strategy in proof of stake could amalgamate these assurances, for instance, providing protection against selfish mining if feasible while adhering to a hard minimum target of 5% participation.

Now, we can also address the distinction between redistributing and burning transaction fees. It is evident that, in expectation, the two are equal: redistributing 50 ETH daily and inflating 50 ETH per day equates to burning 50 ETH each day and inflating 100 ETH daily. The trade-off, once again, lies in the variance. If fees are redistributed, we possess a higher certainty regarding supply, but less certainty regarding security, as we have clarity on the size of the validation incentive. Conversely, if fees are incinerated, we forfeit certainty about supply but gain assurance about the size of the validation incentive and consequently the security level. Burning fees also provides the advantage of minimizing cartel risks, as validators cannot accrue as much by artificially raising transaction fees (e.g., through censorship or via capacity-restricting soft forks). Once more, a hybrid pathway is feasible and might prove optimal, though currently, it appears an approach focused more on burning fees, thereby accepting an uncertain cryptocurrency supply that may see minimal reductions on net during high-usage periods and slight increases on net during low-usage intervals, is preferable. If utilization is sufficiently high, this might even result in subdued deflation on average.