“`html

In the previous Mempool article, I discussed the various types of relay policy filters, their purpose, and the motives that ultimately determine how effective each category of filter is at obstructing the confirmation of different types of transactions. In this article, I will explore the interactions within the relay network when certain nodes have varying relay policies compared to others.

Assuming all factors remain constant, when nodes in the network implement uniform relay policies in their mempools, all transactions ought to disseminate throughout the entire network provided they offer the minimum feerate necessary to avoid eviction from a node’s mempool during periods of significant transaction congestion. This scenario alters when diverse nodes in the network apply differing policies.

The Bitcoin relay network functions on a best-effort basis, utilizing what is referred to as a flood-fill architecture. This signifies that when a transaction is received by one node, it is transmitted to all other nodes it is linked to, excluding the one that it initially received the transaction from. This is an exceedingly inefficient network structure, but within a decentralized context, it guarantees a substantial assurance that the transaction will ultimately reach its intended destination: the miners.

Implementing filters in a node’s relay policy to limit the relaying of otherwise valid transactions theoretically creates friction in the transaction’s propagation, thus undermining the reliability of the network’s ability to perform this function. However, in reality, the situation is more complex.

How Much Friction Prevents Propagation

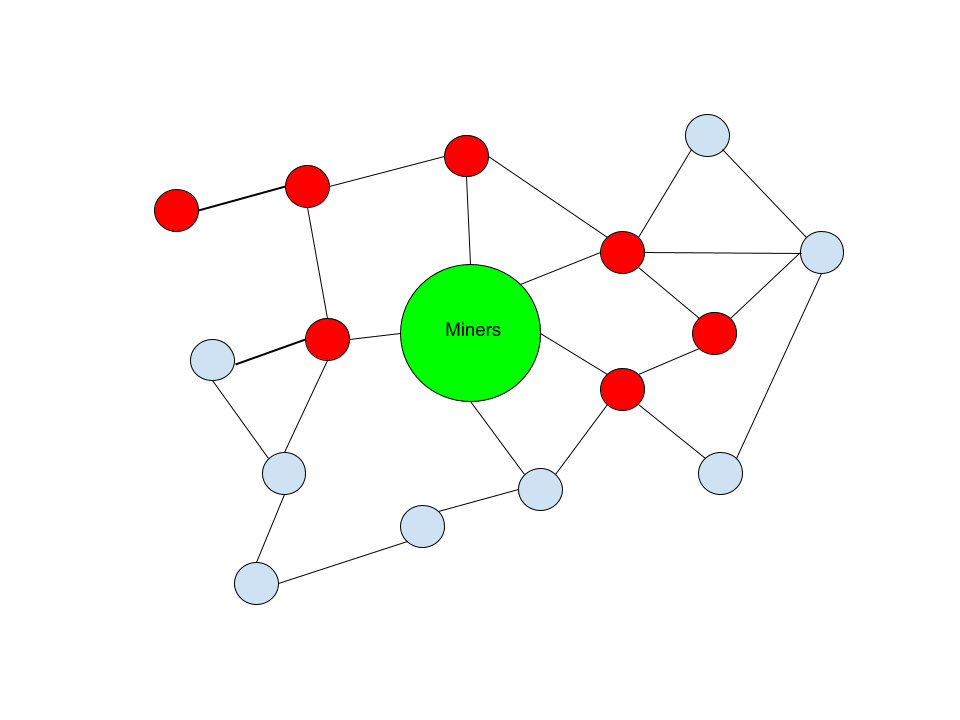

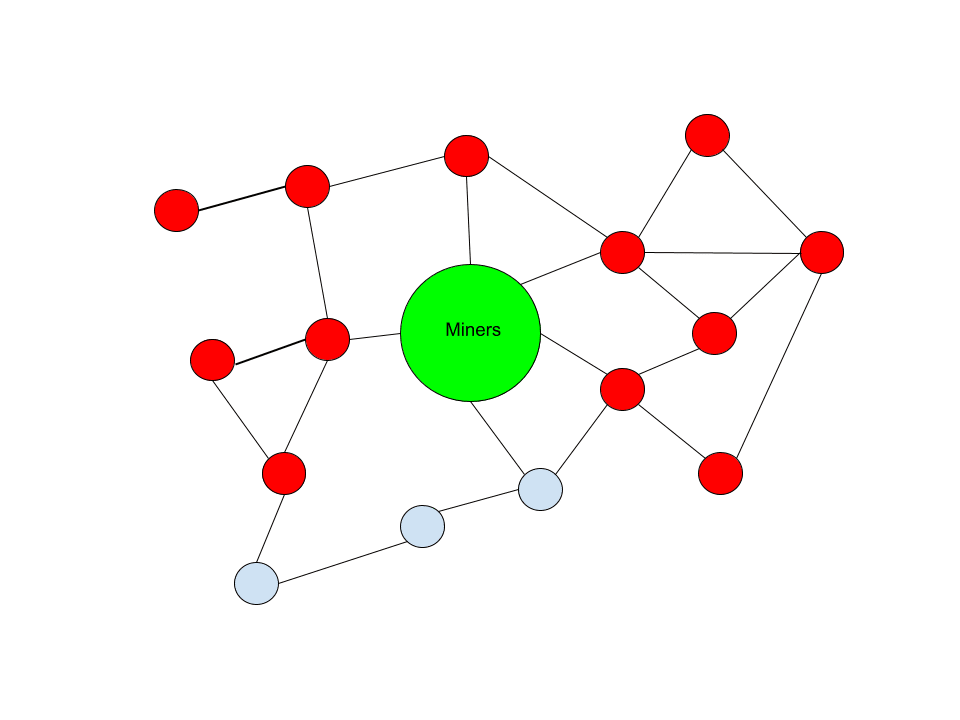

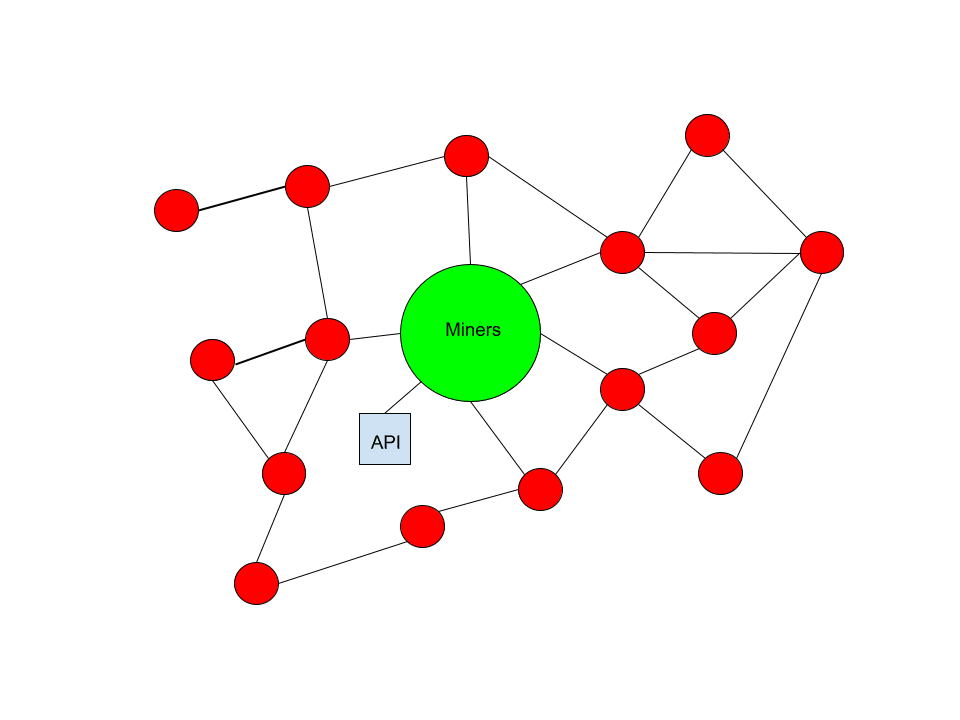

Let us examine a simplified illustration of various network node compositions. In the illustrations below, blue nodes symbolize those that will transmit some arbitrary category of consensus-valid transactions, while red nodes symbolize those that will not transmit these transactions. The collective group of miners is represented in the center, symbolizing where transacting users ultimately desire their transactions to end up for eventual confirmation in the blockchain.

This model depicts a network where nodes refusing to relay these transactions are a clear minority. As illustrated, any node on the network that accepts them has an unobstructed pathway to relay them to the miners. The two nodes attempting to limit the transaction’s propagation across the network have no influence on their eventual reception by miners’ nodes.

In this illustration, you can observe that nearly half of the example network is implementing filtering policies for this category of transactions. Despite this, only a portion of the network propagating these transactions is hindered from accessing miners. The remaining nodes that are not filtering still maintain a clear route to miners. This restriction has introduced some level of friction for a subset of users, yet others can still freely engage in propagating these transactions.

Even for those users impacted by filtering nodes, merely one connection to the other network nodes that are not obstructed from miners (or a direct link to a miner) is required to eliminate that friction. If the actual relay network were to mirror a similar composition to this example, all it would take is a single new connection to resolve the issue.

In this context, merely a minuscule fraction of the network is actively disseminating these transactions. The remaining network is applying filtering measures to obstruct their spread. Nonetheless, even under such circumstances, those nodes that opt not to filter still possess a direct route to relay them to miners.

This minuscule fraction of non-filtering nodes is essential for ensuring their ultimate relay to miners. Preferential peering strategies, namely functionalities aimed at ensuring that your node favors peers utilizing the same software version or relay protocols. These kinds of solutions can assure that peers who will pass something on to others won’t connect with one another and preserve links among themselves across the network.

The Tolerant Minority

As evidenced by these varied illustrations, even when confronted with a substantial majority of the public network participating in the filtering of a particular category of transactions, all that is required for these to successfully traverse the network to miners is a small minority of the network to disseminate and relay them.

These nodes will essentially, through whatever technical mechanism, establish a “sub-network” within the larger public relay network to ensure there are viable pathways from users engaged in these types of transactions to the miners willing to incorporate them in their blocks.

Fundamentally, no measures can be taken to counter this dynamic except for conducting a Sybil attack against all of these nodes, and Sybil attacks only necessitate a single genuine connection to be entirely thwarted. Additionally, a legitimate node forming a vast number of connections with other nodes in the network can significantly elevate the cost of such a Sybil attack. The larger the number of connections it forms, the more Sybil nodes that need to be created to occupy all of its connection slots.

What If There Is No Minority?

So, what occurs if there isn’t a Tolerant Minority? What will become of this class of transactions in such a scenario?

If users continue to desire to create them and offer fees to miners for their inclusion, they will be validated. Miners will simply establish an API. The function of miners is to validate transactions, and their motivation is profit maximization. Miners are not altruistic entities or driven by moral or ideological factors; they operate as businesses. Their primary goal is to generate revenue.

If there are users ready to compensate them for a particular kind of transaction, and the complete public relay network refuses to circulate those transactions to miners for incorporation in blocks, miners will devise an alternative method for users to present those transactions to them.

It is simply the logical action to take as a profit-driven entity when customers are available who wish to pay you.

Relay Policy Is Not A Substitute For Consensus

Ultimately, relay policy cannot effectively censor transactions that are consensus valid, users are willing to pay for, and miners don’t have exceptional reasons to reject the fees that users are eager to provide (such as causing significant damage or harm to nodes on the network, e.g., crashing nodes, disseminating blocks that take hours to verify on a consumer PC, etc.).

If a specific type of transaction is genuinely viewed as undesirable by Bitcoin users and node operators, there is no remedy to prevent them from being validated in the blockchain except by implementing a consensus alteration to render them invalid.

If it were feasible to merely obstruct transactions from being validated through filtering policies enacted on the relay network, then Bitcoin would lack censorship resistance.

Source link

“`