One of the essential attributes frequently desired in a cryptoeconomic algorithm, whether it be a blockchain consensus algorithm such as proof of work or proof of stake, a reputation framework, or a trading mechanism for items like data transmission or file storage, is the concept of incentive-compatibility – the notion that it should be in everyone’s economic advantage to sincerely adhere to the protocol. The crucial fundamental presumption behind this objective is the belief that individuals (or more accurately in this situation nodes) are “rational” – meaning that individuals possess a relatively straightforward and defined set of goals and pursue the optimal strategy to enhance their success in achieving those goals. In game-theoretic protocol crafting, this is often simplified to the assertion that individuals favor monetary gain, as money is a universal tool for advancing nearly any objective. However, in reality, this is not entirely accurate.

Humans, as well as the de facto human-machine hybrids comprising participants of protocols like Bitcoin and Ethereum, are not entirely rational, and there exist specific deviations from rationality that are so widespread among users that they cannot merely be classified as “noise”. Within the social sciences, economics has addressed this issue with the subfield of behavioral economics, which integrates experimental research with a set of new theoretical frameworks, including prospect theory, bounded rationality, defaults and heuristics, and has succeeded in formulating a model that, in certain circumstances, substantially more accurately reflects human behavior.

Within the framework of cryptographic protocols, analyses based on rationality can be considered similarly inadequate, and there are specific parallels among some concepts; for instance, as we will later explore, “software” and “heuristic” are essentially interchangeable terms. Another interesting observation is that we arguably do not possess a precise model of what defines an “agent”, a realization that holds particular relevance for protocols aiming to be “trust-free” or devoid of “single points of failure”.

Conventional models

In conventional fault-tolerance theory, there exist three categories of models employed to ascertain how effectively a decentralized system can endure parts of it deviating from the protocol, whether due to malice or simple malfunction. The first of these is simple fault tolerance. In a simple fault-tolerant system, the concept is that all components of the system can be relied upon to either do one of two things: precisely adhere to the protocol or cease functioning. The system should be constructed to identify failures and recover while rerouting around them in some manner. Simple fault tolerance is typically the most suitable model for evaluating systems that are politically centralized but architecturally decentralized; for instance, Amazon or Google’s cloud hosting. The system should certainly manage one server going offline, yet the creators do not need to consider one of the servers turning malevolent (if that occurs, then an outage is acceptable until the Amazon or Google team manually identifies the issue and deactivates that server).

However, simple fault tolerance is inadequate for describing systems that are not only architecturally but also politically decentralized. What happens when we have a system where we aim to be fault-tolerant against some components of the system behaving improperly, but those components might be overseen by different organizations or individuals, and there exists a lack of trust that all of them will not act maliciously (even though you do trust that, at the very least, two-thirds of them will act honestly)? In this scenario, the appropriate model we seek is Byzantine fault tolerance (named after the Byzantine Generals Problem) – most nodes will sincerely follow the protocol, but a few will diverge, and they can do so in various ways; the presumption is that all deviating nodes are conspiring to undermine you. A Byzantine-fault-tolerant protocol should withstand a limited number of such deviations.

For an illustration of simple and Byzantine fault-tolerance in practice, a suitable use case is decentralized file storage.

Expanding beyond these two scenarios, there exists an even more advanced model: the Byzantine/Altruistic/Rational model. The BAR model enhances the Byzantine model by introducing a simple realization: in real life, there is no clear distinction between “honest” and “dishonest” individuals; everyone is driven by incentives, and if those incentives are substantial enough, even a majority of participants may act dishonestly – especially if the protocol in question weighs individuals’ influence based on economic power, as nearly all protocols do within the blockchain domain. Consequently, the BAR model presumes three categories of actors:

- Altruistic – altruistic actors consistently adhere to the protocol

- Rational – rational actors comply with the protocol when it serves their interests and disregard it otherwise

- Byzantine – Byzantine actors are collectively scheming to undermine you

In practice, protocol developers tend to feel uneasy presuming any specific nonzero amount of altruism, thus the model by which many protocols are evaluated is the even stricter “BR” model; protocols that endure under BR are deemed incentive-compatible (anything that withstands BR also withstands BAR, as an altruist is assured to contribute at least as positively to the protocol’s wellbeing as anyone else, given that benefiting the protocol is their explicit goal).

Note that these are worst-case scenarios that the system must endure, not precise descriptions of reality at all times

To illustrate how this model functions, let us analyze a point advocating for why Bitcoin is incentive-compatible. The aspect of Bitcoin we focus on most is the mining protocol, with miners representing the users. The “correct” strategy outlined in the protocol is to consistently mine on the block with

the utmost “evaluation,” where evaluation is broadly characterized as follows:

- If a block is the origin block, evaluation(B) = 0

- If a block is deemed invalid, evaluation(B) = -infinity

- In other cases, evaluation(B) = evaluation(B.parent) + 1

In real-world scenarios, the impact each block contributes to the overall evaluation fluctuates with difficulty, yet we can set aside these complexities for our straightforward examination. If a block is mined successfully, the miner earns a reward of 50 BTC. Here, we can identify precisely three Byzantine tactics:

- Abstaining from mining altogether

- Mining on a block that is not the one with the highest evaluation

- Attempting to generate an invalid block

The reasoning against (1) is straightforward: if you do not engage in mining, you forfeit the reward. Now, let’s examine (2) and (3). Following the appropriate strategy, you have a likelihood p of creating a valid block with evaluation s + 1 for some s. Conversely, if you adopt a Byzantine tactic, you have a likelihood p of generating a valid block with evaluation q + 1 with q (and if you attempt to generate an invalid block, you have a probability of creating any block with evaluation negative infinity). Therefore, your block is unlikely to be the one with the highest evaluation, which means other miners will not mine on it, and consequently, your mining reward will not be included in the final longest chain. It is noteworthy that this argument does not hinge on altruism; it solely relies on the premise that you have a motive to align with others’ actions if they are also doing so – a classic Schelling point rationale.

The optimum approach to enhance the likelihood that your block will be integrated into the ultimate successful blockchain is to mine on the block that possesses the highest evaluation.

Trust-Free Systems

Another significant division of cryptoeconomic protocols is the classification of so-called “trust-free” centralized systems. Within this group, there exist a few primary categories:

Provably fair gambling

A major concern in online lotteries and gambling platforms is the risk of operator deceit, where the site operator might subtly and imperceptibly “manipulate the odds” to their own advantage. A substantial advantage of cryptocurrency is its capacity to eliminate this issue by formulating an auditable gambling protocol, making any such discrepancies easily detectable. A rough framework for a provably fair gambling protocol is outlined as follows:

- At the start of each day, the platform generates a seed s and publishes H(s), where H represents some standard hashing function (e.g., SHA3)

- When a participant submits a transaction to place a bet, the “dice roll” is computed using H(s + TX) mod n, where TX refers to the transaction utilized to cover the bet and n denotes the quantity of potential outcomes (e.g., for a 6-sided die, n = 6, for a lottery with a 1 in 927 chance of winning, n = 927, and winning games are those where H(s + TX) mod 927 = 0).

- At the conclusion of the day, the platform discloses s.

Users can subsequently verify that (1) the hash revealed at the day’s beginning is indeed H(s), and (2) that the outcomes of the bets correlate with the formulas. Consequently, a gambling platform adhering to this protocol has no means to cheat without facing detection within 24 hours; once it generates s and is required to publish a value H(s), it is essentially compelled to strictly adhere to the defined protocol.

Proof of Solvency

An additional instance of cryptography’s application is the principle of creating auditable financial services (technically, gambling can be categorized as a financial service, but here we focus on services that possess your funds, rather than merely temporarily manipulate them). There are substantial theoretical arguments and empirical support indicating that financial services of this nature are significantly more prone to attempting to deceive their clients; perhaps the most striking example being the MtGox incident, a Bitcoin exchange that ceased operations with over 600,000 BTC of customer funds unaccounted for.

The concept behind proof of solvency works as follows. Assume there exists an exchange with users U[1] … U[n], where user U[i] maintains a balance of b[i]. The total of all balances amounts to B. The exchange aims to demonstrate that it possesses sufficient bitcoins to cover all users’ balances. This constitutes a two-fold challenge: the exchange must concurrently evidence that for a certain B, it holds true that (1) the collective balance of users equals B, and (ii) the exchange holds at least B BTC. The latter is simple to verify; it suffices to sign a message with the private key controlling the bitcoins at that time. The most straightforward means to validate the former is to simply publish everyone’s balances and allow individuals to verify that their balances correspond with the public figures, but this poses a privacy risk; thus, a more refined approach is necessary.

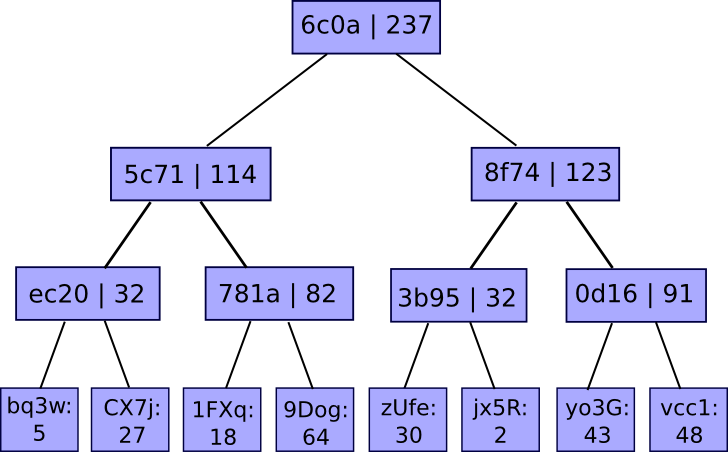

The solution involves, as per usual, a Merkle tree – albeit in this scenario it’s a unique advanced type of Merkle tree referred to as a “Merkle sum tree”. Instead of each node merely possessing the hash of its children, every node contains both the hash of its descendants and the total of the values of its descendants:

The values at the base represent associations of account IDs to balances. The service discloses the tree’s root, and if a user seeks proof that their account is accurately represented in the tree, the service can merely provide them with the branch of the tree associated with their account:

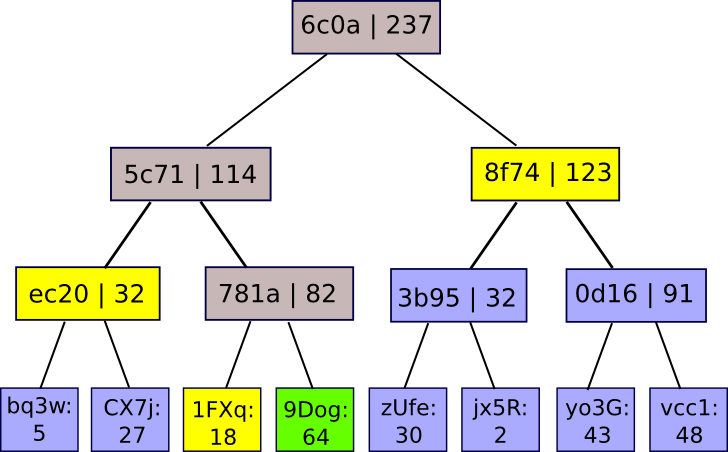

There exist two methods by which the site can deceive, attempting to operate with a fractional reserve. Firstly, it may attempt to have one of the nodes in the Merkle tree falsely total the values of its children. In such an event, as soon as a user seeks a branch incorporating that node, they will realize something is amiss. Secondly, it may try to insert negative values into the tree’s leaves. However, if it engages in this practice, then unless the site provides fraudulent positive and negative nodes that balance each other out (thus undermining the fundamental principle), there will be at least one genuine user whose Merkle branch will include the negative value; generally speaking, successfully maintaining X percent less than the requisite reserve depends on anticipating that a specific X percent of users will never execute the audit process – a scenario that is truly the utmost that any protocol can aspire to, given that an exchange can always simply negate some percentage of its users’ account balances if it anticipates that they will never uncover the deceit.

Multisig

A third use case, one of significant importance, is multisig, or more broadly the notion of multi-key authorization. Instead of your account being under the governance of one private key that could be compromised, there are three keys, of which two are necessary to access the account (or some alternative configuration, potentially featuring withdrawal limits or time-locked withdrawals; Bitcoin does not support such functionalities, but more sophisticated systems do). The prevailing method of implementing multisig thus far is as a 2-of-3: you possess one key, the server retains one key, and you have a third backup key stored securely. During normal operations, when you authorize a transaction, you typically sign it with your key locally and then transmit it to the server. The server conducts a second verification step – possibly involving sending a confirmation code to your phone, and if it confirms that you intended to send the transaction, it signs it as well.

The premise is that such a system can withstand any single fault, including any singular Byzantine fault. If you lose your password, there’s a backup, which in conjunction with the server can retrieve your funds; if your password is compromised, the assailant only has a singular password; and likewise for the loss or theft of the backup. If the service ceases to exist, you have two keys. If the service is breached or turns out to be malicious, it possesses only one. The likelihood of two failures occurring simultaneously is exceedingly low; arguably, you stand a higher chance of passing away.

Fundamental Units

All of the previously discussed arguments rest on one key assumption that appears simple but truly warrants deeper scrutiny: that the core unit of the system is the computer. Each node has the incentive to mine on the block with the highest score and refrain from pursuing any deviant strategy. If the server is compromised in a multisig scenario, then your computer and your backup still encompass 2 out of 3 keys, ensuring your security. The issue with this approach is that it implicitly assumes users maintain complete control over their computers, and that users fully grasp cryptography and are manually validating the Merkle tree branches. In actual practice, this is not true; indeed, the very necessity of multisig in any form is evidence of such, as it acknowledges that users’ computers are susceptible to breaches – a reflection of behavioral-economics insight that individuals may not be entirely in control of their actions.

A more precise model is to regard a node as a combination of two categories of agents: a user, and one or more software providers. Users in nearly every circumstance do not verify their software; even in my own instance, although I confirm every transaction from the Ethereum exodus address, utilizing the pybitcointools toolkit that I created entirely from scratch (others have contributed patches, but even those have been thoroughly reviewed by me), I still rely on (1) the legitimacy of the implementations of Python and Ubuntu that I downloaded, and (2) the integrity of the hardware being free from flaws. Thus, these software providers should be treated as independent entities, and their motives and incentives should be examined as stakeholders in their own right. Meanwhile, users should also be regarded as agents, but as agents equipped with limited technical skills, whose decision-making often consists primarily of selecting which software packages to install instead of which specific protocol rules to adhere to.

The foremost, and most critical, observation is that the notions of “Byzantine fault tolerance” and “single point of failure” should be interpreted in light of this distinction. In theory, multisig eliminates all single points of failure from the management process of cryptographic tokens. However, in practice, that is not how multisig is typically showcased. Currently, most mainstream multisig wallets are web applications, and the entity providing the web application is the very entity managing the backup signing key. What this implies is that, if the wallet provider is indeed compromised or turns out to be unscrupulous, they essentially possess control over two out of three keys – they already hold the first one and can effortlessly acquire the second by implementing a minor modification to the client-side browser application they dispatch to you each time you access the webpage.

In defense of multisig wallet providers, services like BitGo and GreenAddress offer an API, enabling developers to utilize their key management functionality independently of their interface, thereby allowing the two providers to exist as separate entities. Nevertheless, the significance of this form of separation is currently severely understated.

This understanding holds true for provably fair gambling and proof of solvency as well. Specifically, such provably fair protocols ought to have standard implementations, with open-source applications capable of verifying proofs in a standardized format and in a user-friendly manner. Services like exchanges should then adhere to those protocols,and provide evidence that can be validated by these external tools. If a service issues a proof that can solely be validated by its internal tools, that is not significantly better than having no proof whatsoever – slightly improved, given there is a slight chance that deceit may still be uncovered, but not by much.

Software, Users, and Protocols

If we indeed possess two categories of entities, it would be beneficial to outline at least a rough model of their motivations, enabling us to better grasp their probable actions. Typically, from software providers, we can generally anticipate these objectives:

- Maximize profit – during the peak of proprietary software licensing, this aim was straightforward: software firms maximize profits by attracting as many users as possible. The shift towards open-source and freely available software presents numerous advantages, but it complicates the profit-maximization assessment considerably. Presently, software companies primarily generate income through commercial enhancements, the defensibility of which often involves establishing proprietary closed ecosystems. Nonetheless, making one’s software as beneficial as possible remains advantageous, provided it does not conflict with proprietary enhancements.

- Altruism – altruists develop software to assist individuals or to bring to life a certain vision of the world.

- Maximize reputation – nowadays, creating open-source software is frequently seen as a means to enhance one’s resume, aiming to (1) appear more appealing to prospective employers and (2) establish social networks to optimize future opportunities. Corporations can engage in this practice as well, developing free tools to attract users to their websites to promote additional tools.

- Laziness – software developers are unlikely to write code if it can be avoided. The primary effect of this is underinvestment in features that do not benefit their users but would support the ecosystem – such as responding to requests for data – unless the software ecosystem operates as an oligopoly.

- Avoiding legal trouble – this involves adherence to regulations, which may occasionally incorporate anti-features such as mandating identity verification, but the predominant impact of this motivation is a deterrent against overtly deceiving customers (e.g., misappropriating their funds).

Users will not be examined in terms of goals but rather through a behavioral model: users select software from an available pool, download the application, and make decisions from within that software. Influential factors in software selection include:

- Functionality – what is the utility (the economics term “utility”) they can gain from the features that the software offers?

- User-friendliness – particularly crucial is the query regarding how quickly they can begin to perform the tasks they need to accomplish.

- Perceived credibility – users are more inclined to download applications from reputable or at least seemingly reputable sources.

- Prominence – if a software package is referenced more frequently, users are more likely to opt for it. An immediate outcome is that the “official” version of a software package holds a significant advantage over any forks.

- Moral and philosophical considerations – users may have a preference for open-source software for its inherent value, rejecting purely exploitative forks, etc.

Once users download a software application, the primary bias that can be anticipated is that users will adhere to defaults even when it might not serve their interests; beyond this, we have more traditional biases like loss aversion, which we will briefly touch on later.

Let us illustrate how this process operates in practice: BitTorrent. In the BitTorrent protocol, users can obtain files from one another in a decentralized manner, but for a user to download a file, there must be another user uploading (“seeding”) it – and this action lacks adequate incentives. In fact, it incurs non-trivial costs: bandwidth usage, CPU resource utilization, copyright-related legal threats (including the risk of having one’s internet connection terminated by their ISP, or possibly facing a lawsuit). Yet individuals continue to seed – significantly insufficiently, but they do.

Why? The situation is aptly explained by the two-layer model: software developers aim to enhance their software’s usefulness, hence they include the seeding functionality as a default, and users are generally too complacent to deactivate it (and some users are intentionally altruistic, although the stark discrepancy between the willingness to torrent copyrighted content and the readiness to support artists indicates that most participants are indifferent). Message-sending in Bitcoin (i.e., to data requests like getblockheader and getrawtransaction) is also altruistic yet similarly explainable, as is the inconsistency between transaction fees and current economic predictions regarding transaction fees.

Another instance is proof of stake algorithms. Proof of stake algorithms face the (often) shared vulnerability of possessing “nothing at stake” – meaning, in the event of a fork, the default behavior is to attempt to vote on all chains, allowing an assailant to merely overpower all altruists who vote on a single chain, rather than having to contend with both altruists and rational actors as in proof of work. Here, we once again observe that this does not imply that proof of stake is entirely flawed. If the stake is predominantly grasped by a limited number of sophisticated parties, those parties will have their holdings in the currency as motivation not to engage in forks, and if the stake is held by a far greater number of average individuals, there would need to be a uniquely malevolent software provider who goes to the trouble of integrating a multi-voting feature and promotes it so that potential users are actually aware of it.

Nevertheless, if the stake is retained in custodial wallets (e.g., Coinbase, Xapo, etc.) that do not legally belong to the entities, but are specialized professional organizations, then this argument falters: they possess the technical capability to multi-vote, and have a low incentive against doing so, particularly if their businesses are not “Bitcoin-centric” (or Ethereum-centric, or Ripple-centric) and accommodate multiple protocols. There even exists a probabilistic multi-voting strategy that such custodial entities can employ to achieve 99% of the advantages of multi-voting without the risk of being caught. Therefore, the effective viability of proof of stake to a moderate degree relies on technologies that empower users to securely maintain control of their own coins.

Darker Consequences

What we observe from the default effect isis fundamentally a specific degree of centralization, playing a constructive role by guiding users’ default behavior towards a socially advantageous action and subsequently addressing what would otherwise be a market shortcoming. Now, if software brings forth some advantages of centralization, we could also anticipate some of the adverse effects associated with centralization. A notable instance is fragility. Theoretically, Bitcoin mining functions as an M-of-N protocol where N is in the thousands; performing the combinatorial calculations indicates that the likelihood of even 5% of the nodes diverging from the protocol is virtually nonexistent, thus Bitcoin should theoretically exhibit nearly flawless reliability. However, in practice, this assertion is incorrect; Bitcoin has experienced at least two disruptions within the past six years.

For those who may not recall, the two incidents were as follows:

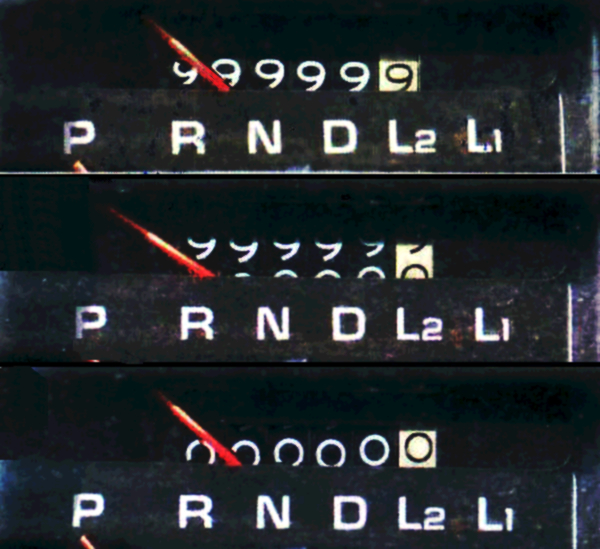

Driver of a 43-year-old automobile exploits integer overflow flaw, sells it for 91% of the original purchase price passing it off as new

- In 2010, an anonymous user generated a transaction featuring two outputs, each holding slightly more than 263 satoshis. The combined value of these outputs was just over 264, and an integer overflow caused the total to wrap around to approximately zero, leading the Bitcoin client to believe that the transaction only released the same minimal amount of BTC that was input, thus appearing legitimate. The glitch was resolved, and the blockchain was reverted after nine hours.

- In 2013, a new release of the Bitcoin client inadvertently addressed a bug where a block that made over 5000 calls to a specific database resource would trigger a BerkeleyDB error, causing the client to refuse the block. Such a block soon emerged, prompting new clients to accept it while older clients rejected it, resulting in a fork. The fork was rectified within six hours; however, during that time, $10000 worth of BTC was unlawfully taken from a payment service provider in a double-spend exploit.

In both scenarios, the network was capable of failing because, despite the presence of thousands of nodes, there was merely one software implementation governing them all – potentially the ultimate fragility in a network frequently praised for its antifragile properties. Alternative implementations such as btcd are progressively being adopted, yet it will take years before Bitcoin Core’s dominance is even remotely diminished; and even then, fragility will still remain relatively high.

Endowment Effects and Defaults

A significant set of biases to consider from the user perspective includes the ideas of the endowment effect, loss aversion, and the default effect. These three concepts often intersect but differ somewhat from one another. The default effect is typically most accurately described as a tendency to maintain one’s current strategy unless there is a considerable incentive to change – essentially, an artificial psychological switching cost of some value ε. The endowment effect refers to the inclination to perceive items as more valuable when one already possesses them, while loss aversion denotes the inclination to prioritize avoiding losses over pursuing gains – empirical evidence suggests that the scaling factor appears to hover consistently around 2x.

The ramifications of these effects become most pronounced in multi-currency environments. For instance, consider employees compensated in BTC. It becomes evident that when individuals receive payments in BTC, they are significantly more inclined to retain those BTC compared to the likelihood of purchasing BTC had they been paid in USD; this is partly due to the default effect, and partly because being paid in BTC leads individuals to “think in BTC,” creating a risk of loss if they convert to USD and the value of BTC subsequently appreciates. Conversely, when paid in USD, individuals are more focused on the USD-value of their BTC. This also holds true for smaller token systems; if someone is paid in Zetacoin, they are likely to cash out into BTC or another cryptocurrency, though the likelihood does not reach 100%.

The dynamics of loss aversion and default effects present compelling arguments in support of the thesis that a highly polycentric currency system is likely to persist, contrary to Daniel Krawisz’s assertion that BTC is the singular currency to dominate them all. There exists a clear incentive for software developers to create their own coins even if the protocol could function equally well on top of an existing currency: they can conduct a token sale. StorJ serves as the latest example. Nevertheless, as Daniel Krawisz argues, it is feasible to fork such an “app-coin” and launch a version atop Bitcoin, which would theoretically be superior due to Bitcoin’s liquidity as an asset for storing funds. The reason this scenario has a high probability of not materializing stems from the fact that users tend to adhere to defaults, and by default users will utilize StorJ alongside StorJcoin since that is what the client promotes, and the initial StorJ client and site as well as its ecosystem will garner the majority of the attention.

This argument does, however, falter under certain circumstances: should the fork be backed by a powerful entity. A recent illustration of this is the situation with Ripple and Stellar; though Stellar is a fork of Ripple, it is supported by a major corporation, Stripe, thereby diminishing the advantage held by the original software version due to significantly greater visibility. In such instances, the outcome remains uncertain; perhaps, as frequently observed in social sciences, we will simply need to await empirical data to discover the resolution.

The Path Ahead

Building on specific psychological characteristics of individuals in cryptographic protocol design is a precarious endeavor. The rationale for maintaining simplicity in economic models, and even more so in cryptoeconomics, is that although desires, such as the pursuit of acquiring additional currency units, do not encapsulate the entirety of human motivation, they represent a notably robust component, and some may argue the only reliable component we can depend on. Moving forward, education might deliberately endeavor to tackle what we recognize as psychological anomalies (in fact, it already does), shifts in culture might engender transformations in morals and ideals, and notably in this context, the entities involved are “fyborgs” – functional cyborgs, or humans whose actions are entirely mediated by machines that serve as intermediaries between them and the internet.

Nevertheless, there are certain core attributes of this model – the notion of cryptoeconomic systems as two-tiered frameworks featuring software and users as agents, the emphasis on simplicity, and so forth, that may be dependable. At the very least, we should strive to recognize situations where our protocol is secure under the BAR model, yet vulnerable under a scenario where a handful of centralized entities are effectively regulating everyone’s access to the system. The model also underscores the significance of “software politics” – gaining insights into the forces that influence software development and striving to devise frameworks that provide software developers with the most favorable incentives (or ultimately create software that is most beneficial to the successful execution of the protocol). These challenges remain unaddressed by Bitcoin and Ethereum; possibly, a future system will achieve at least moderate improvement.