Particular appreciation to: Robert Sams, Gavin Wood, Mark Karpeles and numerous cryptocurrency skeptics in online discussions for aiding in the formulation of the ideas presented in this article

Should you inquire with the typical cryptocurrency or blockchain aficionado about the primary singular fundamental benefit of the technology, there is a strong likelihood that they will provide one specific expected response: it eliminates the necessity for trust. In contrast to conventional (financial or other) frameworks, where reliance on a specific entity is needed to manage the records of who possesses what amount of assets, who has ownership of a certain internet-of-things-enabled instrument, or what the current status is of a specific financial agreement, blockchains facilitate the creation of systems that allow you to monitor the solutions to those inquiries without needing to rely on anyone whatsoever (at least in theory). Rather than being subject to the caprices of any singular arbitrary participant, an individual utilizing blockchain technology can find solace in the assurance that the state of their identity, assets or device ownership is securely and safely preserved in a highly secure, trustless distributed ledger Backed By Math™.

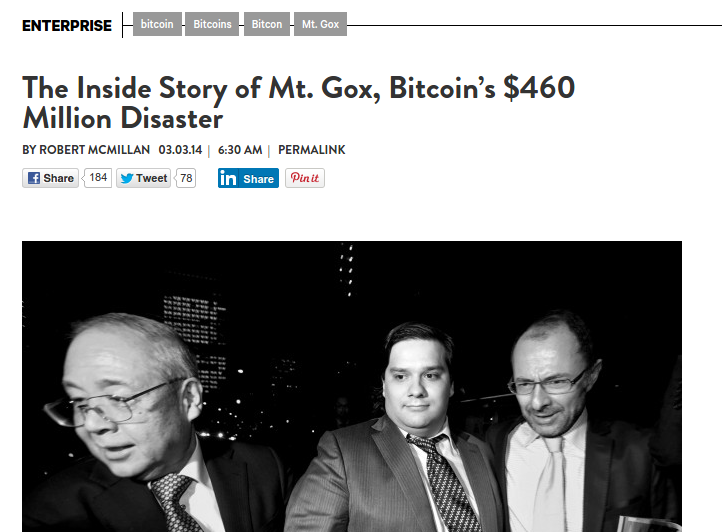

However, juxtaposed with this, one often encounters the common critique that one might observe in forums like buttcoin: what precisely is this “trust issue” that individuals are so concerned about? Ironically, contrary to “crypto land,” where exchanges appear to frequently vanish with millions of dollars in customer assets, sometimes after seemingly secretly being in debt for years, businesses in the physical world do not seem to face any of these dilemmas. Certainly, credit card fraud occurs, and is a significant concern at least among Americans, but the total global loss is merely $190 billion – less than 0.4% of global GDP, compared to the MtGox loss that appears to have cost potentially more than the value of all Bitcoin transactions in that year. At least in the industrialized world, if you deposit your money in a bank, it’s secure; even if the institution encounters issues, your assets are in most situations safeguarded up to over $100,000 by your national equivalent of the FDIC – even in the instance of the Cyprus depositor haircut, everything up to the deposit insurance threshold was preserved. Viewed from this angle, one can easily recognize how the conventional “centralized system” is adequately serving individuals. So what’s the significant concern?

Trust

Initially, it’s essential to emphasize that skepticism is not exclusively the reason for utilizing blockchains; I enumerated several considerably more ordinary applications in the earlier segment of this series, and once you begin to consider the blockchain merely as a database that anyone can access any segment of but where each unique user can solely write to their own small section, and where you can also execute programs on the data with assured execution, it becomes quite conceivable even for a completely non-ideological perspective to perceive how the blockchain could eventually establish itself as a rather unremarkable and unexciting technology akin to MongoDB, AngularJS and continuation-based web servers – not at all equating to the revolutionary nature of the internet itself, but still quite impactful. Nevertheless, many individuals are drawn to blockchains particularly due to their attribute of “trustlessness,” and thus this trait merits exploration.

To begin, let’s attempt to clarify this rather intricate and impressive notion of “trust” – and, concurrently, trustlessness as its counterpart. What precisely constitutes trust? Dictionaries in this context tend not to offer particularly precise definitions; for instance, if we consult Wiktionary, we find:

- Reliance on or confidence in a person or quality: He needs to restore her trust if he is ever going to win her back.

- Dependence on something that will occur in the future; hope.

- Confidence in the future remuneration for goods or services rendered; credit: I was out of funds, but the landlady allowed me to have it on trust.

There is also the legal interpretation:

A relationship established at the instruction of an individual, in which one or more persons retain the individual’s assets under specific obligations to utilize and safeguard it for the advantage of others.

Neither definition is sufficiently precise or complete for our needs, but they both get us relatively close. If we seek a more formal and abstract definition, we can propose one as follows: trust is a model of a specific person or group’s anticipated behavior, coupled with the adaptation of one’s own actions in accordance with that model. Trust represents a belief that a particular person or collective will be influenced by a distinct set of objectives and incentives at a certain moment, and the readiness to engage in actions that depend on that model being accurate.

Just from the more standard dictionarydefinition, one might fall into the illusion of believing that trust is inherently illogical or unreasonable, and that one ought to strive to trust as minimally as feasible. However, in actuality, one can observe that such reasoning is entirely erroneous. Individuals hold convictions about everything; indeed, there is a collection of theorems that essentially suggest if you are a completely rational being, you must possess a probability for every conceivable assertion and adjust those probabilities according to specific guidelines. Thus, if you hold a belief, it becomes irrational not to act accordingly. If, within your personal mental framework concerning the actions of people in your vicinity, there exists more than a 0.01% likelihood that leaving your door unsecured may lead to someone stealing $10,000 worth of possessions from your home, and you estimate the inconvenience of carrying your key to be $1, then you ought to secure your door and take the key with you to work. Conversely, if there is less than a 0.01% chance of someone breaking in and stealing that amount, it is irrational to secure the door.

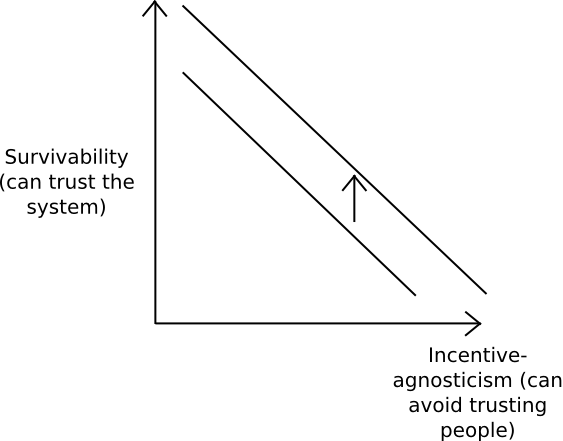

“Trustlessness” in its ultimate form does not exist. In any system overseen by humans, there exists a theoretical arrangement of motivations and incentives that would enable those humans to successfully conspire against you. Therefore, if you place your trust in the system’s functionality, you are inherently trusting the overall group of individuals not to possess that specific combination of motivations and incentives. Nonetheless, this does not imply that the pursuit of trustlessness is not a valuable goal. When a system purports to be “trustless,” it is genuinely attempting to broaden the array of motivations that individuals can have while still ensuring a particular low probability of failure. Conversely, when a system claims to be “trustful,” it is striving to lower the probability of failure based on a specific set of motivations. Hence, we can observe that “trustlessness” and “trustfulness,” at least as objectives, are effectively the very same concept:

|

It is noteworthy that in practice, the two might differ in connotation: “trustless” systems often endeavor more rigorously to enhance system trustworthiness based on a model where little is known regarding individuals’ motivations, while “trustful” systems typically exert greater effort to improve system trustworthiness based on a model where a significant amount is known about individuals’ motivations and where those motivations tend to be, with higher certainty, honest. Both approaches are likely to be beneficial.

Another crucial aspect to highlight is that trust is not a binary concept, nor is it merely scalar. Instead, it is critically important what you are placing your trust in others to do or refrain from doing. A particularly counterintuitive observation is that it is quite feasible, and often occurs, that we trust someone not to do X, but do not trust them not to commit Y, even though the consequences of that person doing X may be worse for you than if they committed Y. You trust thousands of individuals each day not to suddenly produce a knife from their pockets as you pass by and stab you, yet you do not trust complete strangers to safeguard $500 in cash. The reasoning is clear: no one has an incentive to ambush you with a knife, and there exists a strong disincentive against such behavior. However, if someone has your $500, they possess a $500 incentive to flee with it, and they can quite easily elude capture (and if apprehended, the penalties aren’t that severe). Sometimes, even when incentives in both situations are comparable, such unexpected results can arise simply because you possess nuanced awareness of another’s morality; as a general notion, you can trust that individuals are adept at preventing themselves from engaging in actions deemed “obviously wrong,” yet morality often becomes frayed at the edges where individuals can convince themselves to blur the boundaries of the grey (consider Bruce Schneier’s concept of “moral pressures” in Liars and Outliers and Dan Ariely’s The Honest Truth about Dishonesty for further insight into this matter).

This particular subtlety of trust is of direct significance in finance: although, following the 2008 financial crisis, there has indeed been a rise in public distrust towards the financial system, the distrust felt by the general populace is not rooted in a belief that there is a high risk of the bank openly stealing people’s assets and altering everyone’s bank balance to zero. That would certainly be the worst possible action they could take (except for the CEO springing at you upon entering the bank branch and stabbing you), but it is not a likely action for them to undertake: it is exceedingly illegal, easily detectable, and would result in long-term incarceration for those implicated – and, just as importantly, it is difficult for a bank CEO to rationalize to themselves or their family that they remain a morally upright individual after committing such an act. Instead, our fear is that the banks will employ one of many more subtle and underhanded tactics, such as persuading us that a specific financial product has a certain risk profile while concealing black swan risks. Even while we constantly worry that large corporations will engage in actions that are moderately questionable, we simultaneously possess a reasonable assurance that they will not commit anything extremely outright malevolent – at least not most of the time.

In today’s society, where are we lacking trust? What is our understanding of people’s motivations and goals? Who do we depend on yet do not trust, who could serve as reliable but are not trusted, what precisely do we fear they might do, and how can decentralized blockchain technology assist?

Finance

There are several responses. Firstly, in some instances, it turns out that the centralized giants still very much cannot be relied upon. In contemporary financial systems, particularly banks and trading platforms, there exists a notion of “settlement” – fundamentally, a procedure after a transaction or trade is executed, the end result of which is that the assets you purchased actually become legally yours from a property-rights standpoint. Following the trade and prior to settlement, all you possess is a promisethat the counterparty will compensate – a legally enforceable commitment, yet even legal assurances are meaningless when the counterparty is bankrupt. If a deal yields you an anticipated profit of 0.01%, and you are dealing with a firm that you believe has a likelihood of 1 in 10,000 of becoming insolvent on any single day, then a one-day settlement period significantly changes the outcome. The same scenario exists in global transactions, but in this case, the parties genuinely do not trust each other’s motives, as they operate in different jurisdictions, some of which have legislation that is weak or even corrupt.

Historically, the legal ownership of assets was determined by possession of a physical document. Nowadays, the ledgers are digital. But then, who manages the digital ledger? And can we place our trust in them? In the financial sector, more than anywhere else, the combination of a high stake-to-expected-return ratio alongside the significant potential for profit from unethical behavior elevates trust-related risks beyond that of almost any other legal white-market sector. Consequently, could decentralized, reliable computing platforms – and particularly, politically decentralized reliable computing platforms, effectively address this issue?

Many individuals believe so. However, in these discussions, analysts like Tim Swanson have highlighted a possible weakness within the “fully open” PoW/PoS model: it’s somewhat excessively accessible. Partly, there may be regulatory concerns regarding a settlement system based on a completely anonymous group of consensus participants; more importantly, though, having restrictions in place can reduce the likelihood that the participants will conspire and disrupt the system. Who would you genuinely trust more: a consortium of 31 rigorously vetted banks that are clearly distinct entities, situated in various nations, not controlled by the same investment conglomerates, and are legally bound if they collude against you, or a collection of mining companies of uncertain quantity and reputation, 90% of whose chips might be manufactured in Taiwan or Shenzhen? For traditional securities settlement, the response that most people would provide seems fairly obvious. However, ten years from now, if a particular set of miners or anonymous stakeholders of a certain currency proves its reliability, eventually banks may eventually embrace even the more “purely cryptoanarchic” format – or they may not.

Interaction and Shared Understanding

An additional crucial aspect is that even if each individual has a set of entities they trust, not everyone possesses the identical set of entities. IBM is perfectly comfortable placing its trust in IBM, yet IBM likely wouldn’t prefer its essential infrastructure to operate on Google’s cloud. More critically, neither IBM nor Google may prefer to have their crucial infrastructure running on Tencent’s cloud, thereby potentially elevating their vulnerability to the Chinese government (and similarly, particularly after the recent NSA controversies, there’s been a rising interest in keeping one’s data outside the US, although it should be noted that much of this concern revolves around privacy, not defense against active intrusion, and blockchains are generally more effective at providing the latter rather than the former).

So, what if IBM and Tencent aspire to create applications that extensively interact? One solution is to directly access each other’s services via JSON-RPC, or some analogous framework, but as a programming environment, this has its limitations; each program must either operate within IBM’s space, leading to a 500-millisecond round-trip to send a request to Tencent, or reside in Tencent’s domain, resulting in a 500-millisecond delay to reach IBM. Reliability must also drop below 100%. One potential resolution that may be advantageous in certain scenarios is to have both code pieces function within the same execution environment, even if administered by different parties – yet, in that case, the shared execution environment must be trusted by both sides. Blockchains appear to provide an ideal solution, at least for some scenarios. The most significant advantages may arise when a vast number of users need to engage; when it’s just IBM and Tencent, they can easily create a tailored bilateral system, but when N companies are collaborating, you would need either N2 bilateral systems among every pairing of companies, or you can more efficiently establish a single shared system for all – and that system could as well be called a blockchain.

Trust for the General Public

The second argument for decentralization is more nuanced. Instead of focusing on the absence of trust, here we underscore the barrier to entry in establishing a center of trust. Certainly, billion-dollar enterprises can effectively become centers of trust, and indeed they typically function quite well – with a few noteworthy exceptions that we will explore later. However, their capacity to achieve this comes at a significant cost. Although the fact that numerous Bitcoin businesses have managed to abscond with their clients’ assets is sometimes seen as a criticism of the decentralized economy, it is rather something entirely different: it is a critique of an economy with minimal social capital. It indicates that the substantial level of trust mainstream institutions enjoy today is not merely a result of powerful individuals being particularly nice and technology enthusiasts being less so; rather, it is the outcome of centuries of social capital accumulated over a protracted process that would require many years and trillions of dollars in investments to replicate. Frequently, these institutions behave cooperatively solely because they are regulated by governments – and that regulation, in turn, is not without considerable secondary costs. Absent that accumulation of social capital, well, we simply find ourselves in this situation:

And lest you suppose that such occurrences are a distinctive characteristic of”cryptoland”, back in the tangible world we also observe this:

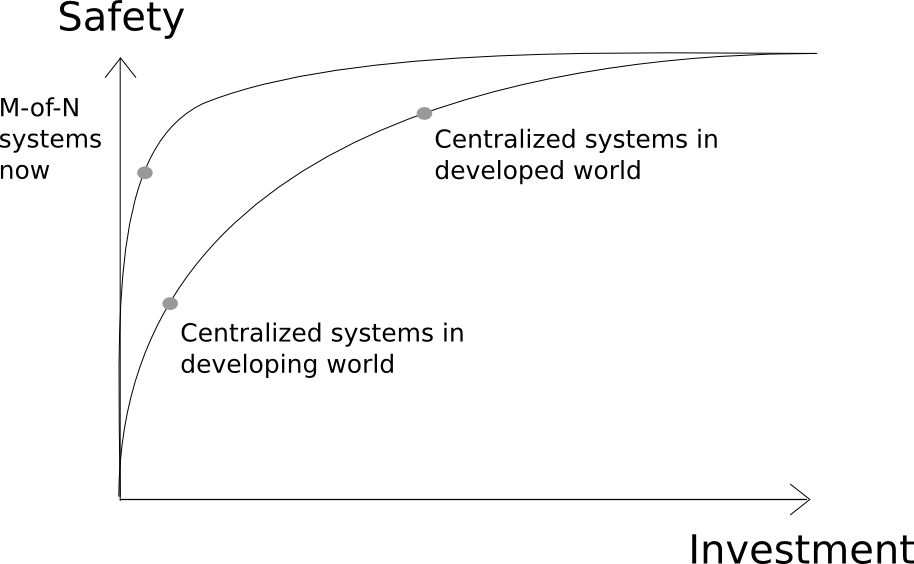

The primary promise of decentralized technology, from this perspective, is not to establish systems that are even more reliable than current major entities; a glance at fundamental statistics in the developed regions reveals that many such systems can reasonably be regarded as “trustworthy enough”, given that their yearly failure rate is low enough for other factors to be more significant in deciding which platform to adopt. Instead, the primary vow of decentralized technology is to offer a shortcut for future application creators to reach their goals more swiftly:

Historically, establishing a service that manages crucial customer data or substantial sums of customer funds has necessitated a high level of trust, thus requiring a significant amount of effort – some involving compliance with regulations, some persuading a recognized collaborator to lend their brand, some investing in very pricey suits and leasing fictitious “virtual office space” in the heart of urban centers like New York or Tokyo, and some simply being a well-established company that has consistently satisfied customers for many years. If you’re seeking to be trusted with millions, you better be ready to invest millions.

Conversely, with blockchain technology, the exact contrary might hold true. A 5-of-8 multisig formed from a group of random individuals worldwide may possess a lower risk of failing than all but the most massive entities – and at a minuscule fraction of the cost. Blockchain-enabled applications enable developers to demonstrate their integrity – by establishing a system where they wield no more control than the users. If a collection of primarily 20-to-25-year-old college dropouts were to declare the launch of a new prediction market and request people to deposit millions through bank transfers, they would likely be justifiably met with skepticism. However, with blockchain technology, they can introduce Augur as a decentralized application, assuring the entire globe that their chance of absconding with everyone’s funds is tremendously diminished. Imagine what would happen if this particular group was located in India, Afghanistan, or even Nigeria. Without being a decentralized application, they would likely struggle to earn anyone’s trust. Even in prosperous regions, the less effort needed to persuade users of your trustworthiness, the more you can focus on advancing your actual product.

Subtler Subterfuge

Ultimately, we circle back to the large corporations. It is indeed a reality, in our contemporary world, that sizable companies are becoming increasingly distrusted – they face rising skepticism from regulators, mounting mistrust from the public, and greater wariness amongst themselves. Yet, at least in the developed areas, it appears obvious that they are unlikely to arbitrarily wipe out individuals’ balances or cause their devices to malfunction in capricious ways for amusement. So, if we have doubts about these giants, what is it we fear they might do? Trust, as mentioned previously, is not simply a binary or a quantifiable measure; it represents a forecast of another’s expected behavior. Thus, what potential failure scenarios exist in our evaluation?

The response typically stems from the notion of base-layer services, as detailed in the previous segment of this series. Certain types of services possess qualities that (1) result in other services relying on them, (2) exhibit significant switching costs, and (3) generate substantial network effects. In such scenarios, if a private firm managing a centralized service establishes a monopoly, they enjoy considerable freedom regarding their actions to safeguard their own interests and to entrench their position at the core of society – often to the detriment of everyone else. The most recent incident showcasing this risk occurred just last week, when Twitter severed video streaming service Meerkat’s access to its social network API. Meerkat’s infringement: enabling users to effortlessly import their social contacts from Twitter.

When a service attains monopoly status, it is motivated to preserve that monopoly. Whether that involves hindering the survival of companies attempting to innovate on the platform in a manner that competes with its offerings, or restricting users’ access to their own data within the system, or creating an easy entry point but a challenging exit, there are numerous opportunities to gradually and subtly undermine users’ freedoms. Furthermore, we increasingly lack faith in companies to refrain from such actions. Conversely, utilizing blockchain infrastructure provides a means for an application developer to pledge against untrustworthy behavior, indefinitely.

… And Laziness

In certain instances, there is another worry: what happens if a specific service ceases operations? The quintessential example here is the various versions of “RemindMe” services, whereby you can request them to deliver a specific message at a certain point in the future – perhaps in a week, potentially in a month, and conceivably in 25 years. However, in the scenario of a 25-year time span (and realistically even the 5-year case), all currently available services of that nature are essentially futile for a rather evident reason: there is no assurance that the company managing the service will remain operational in 5 years, let alone 25. Being skeptical of individuals disappearing is logical; for someone to vanish, they do not even need to be intentionally harmful – they merely must exhibit lethargy.

This presents a significant issue on the internet, where 49% of documents referenced in court rulings have become inaccessible due to the servers hosting the pages no longer existing.longer online, and to achieve that goal initiatives like IPFS are attempting to tackle the issue through a politically decentralized content storage network: instead of identifying a file by the name of the organization that governs it (which an address like “https://blog.ethereum.org/2015/04/13/visions-part-1-the-value-of-blockchain-technology/” effectively does), we identify the file by its hash, and when a user requests the file, any node on the network can supply it – in the project’s own terms, creating “the permanent web”. Blockchains represent the permanent web for software agents.

This is especially significant in the realm of the internet of things; in a recent IBM report, one of their primary worries regarding the default option for internet of things infrastructure, a centralized “cloud”, that they point out is as follows:

While numerous companies are eager to penetrate the market for intelligent, connected devices, they have yet to realize that exiting is extremely difficult. While consumers upgrade smartphones and PCs every 18 to 36 months, the expectation is for door locks, LED bulbs, and other fundamental components of infrastructure to endure for years, even decades, without requiring replacement … In the IoT landscape, the expenses associated with software updates and fixes in products long outdated and discontinued will burden the financial statements of corporations for decades, often extending even beyond the obsolescence of the manufacturer.

From the perspective of the manufacturer, the necessity to uphold servers to manage remaining instances of outdated products is an irritating cost and burden. From the consumer’s standpoint, there is always the persistent anxiety: what if the manufacturer simply neglects this duty and vanishes without ensuring continuity? Having fully autonomous devices that self-manage using blockchain infrastructure appears as a reasonable solution.

Conclusion

Trust is a complex matter. We all wish, at least to some extent, to navigate life without it, and be assured that we can accomplish our objectives without incurring the risk of others’ misconduct – much like every farmer longs for their crops to thrive without the concern of unpredictable weather and sunlight. However, economies necessitate collaboration, and collaboration involves interacting with others. Nevertheless, the inability to achieve a definitive conclusion does not suggest the futility of the journey, and in any scenario, it remains a valuable endeavor to determine how to minimize the likelihood of systemic failures, regardless of our framework.

The decentralization of the type outlined here is not common in the tangible world primarily due to the high costs of duplication, and achieving consensus is challenging: you wouldn’t want to visit five out of eight government offices to obtain your passport, and organizations where every decision is made by a large executive board typically experience a quick decline in efficiency. In the realm of cryptography, however, we benefit from four decades of rapid advancements in affordable computer hardware capable of executing billions of processing cycles per second in silicon – thus, it is reasonable to at least consider the theory that the optimal compromises might be dissimilar. This is, in certain aspects, the ultimate wager of the decentralized software industry – now let’s see how far we can push it.

The next installment of the series will explore the future of blockchain technology from a technical viewpoint, and illustrate what decentralized computation and transaction processing platforms may resemble in a decade.