Company Name: Gridless

Founders: Janet Maingi, Erik Hersman, and Philip Walton

Date Established: August 2022

Headquarters Location: United States | Operations in Kenya, Malawi, and Zambia

Employee Count: 10

Website: https://gridlesscompute.com/

Public or Private? Private

Gridless not only mines bitcoin but also aids in the electrification of rural Africa, significantly enhancing the lives of individuals who previously lacked access to power or could not afford it.

Co-founder Janet Maingi shared with Bitcoin Magazine how the facilities operated by the company in Kenya, Malawi, and Zambia create a triple benefit for the business, the Bitcoin network, and the communities that are positively impacted by Gridless’ activities.

“Our goal is to mine Bitcoin profitably,” Maingi conveyed to Bitcoin Magazine. “Simultaneously, we engage in two additional efforts: we extend electrification to remote areas of Africa and we decentralize the Bitcoin network, which has historically been largely centralized in North America and China.”

In just over two years, Gridless has established a new benchmark for the type of influence a Bitcoin mining enterprise can exert, demonstrating to the world that Bitcoin mining can forge a mutually beneficial relationship with the communities it serves and that it can act as a catalyst for human progress.

I met with Maingi face-to-face in Kenya following this year’s Africa Bitcoin Conference to explore the work she does and the effect it has on the communities it reaches.

A transcript of our exchange, condensed for brevity and clarity, is provided below.

Frank Corva: How does Gridless contribute to electrifying Africa?

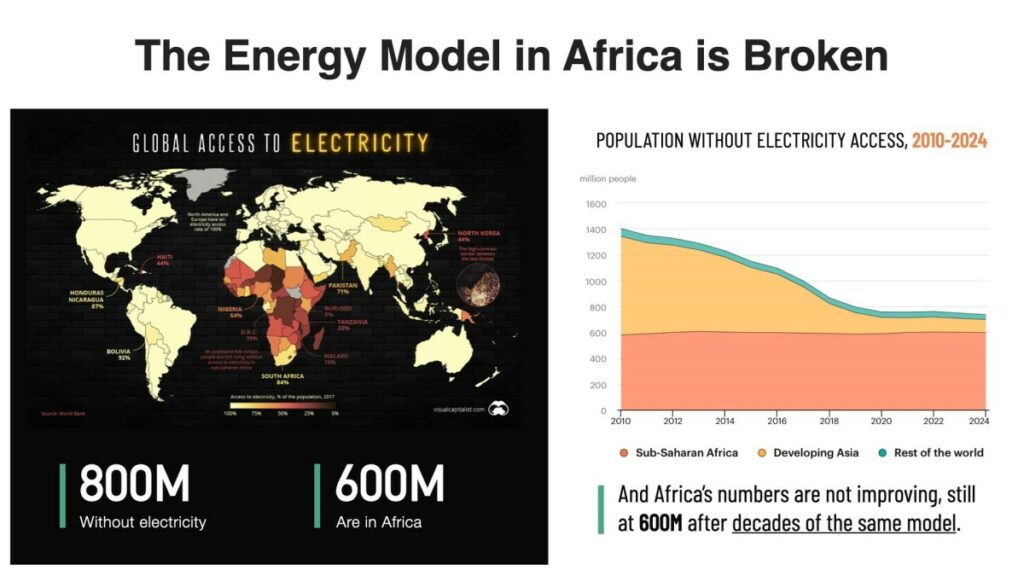

Janet Maingi: Approximately 600 million Africans lack access to electricity. That’s around two-thirds of our population. The private sector has intervened because the main power grids do not extend to everyone on the continent.

Larger cities such as Nairobi or Mombasa have electric supply, but if you venture into rural Africa, people often have no access to power due to distribution obstacles.

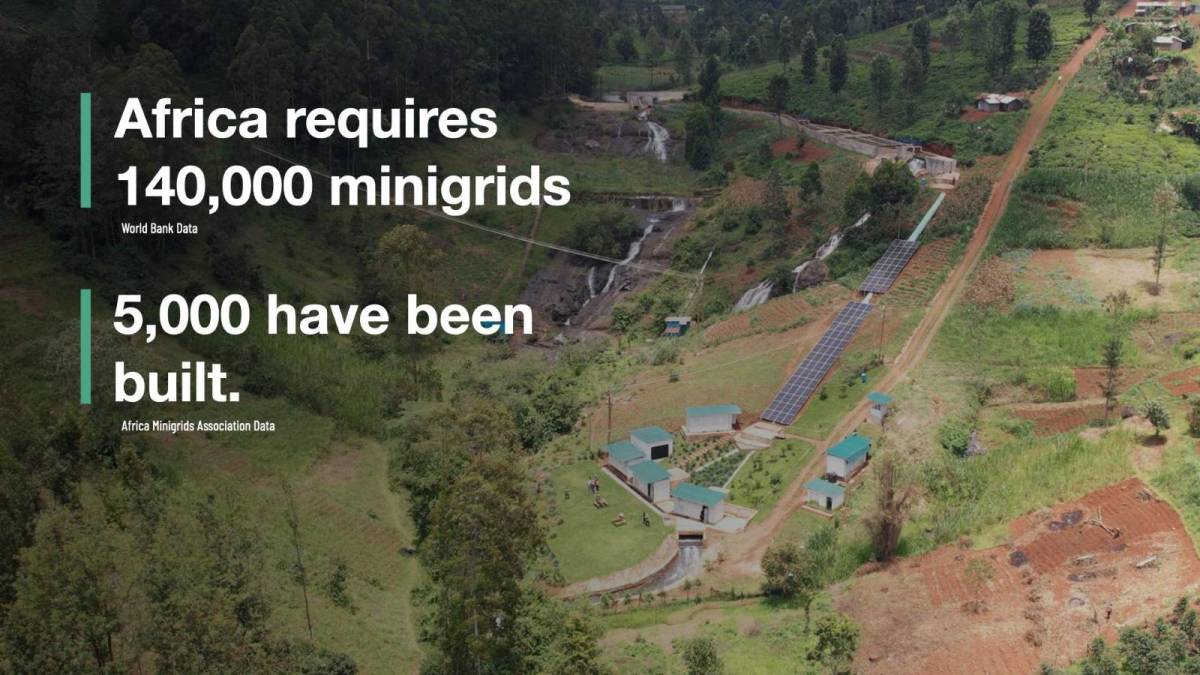

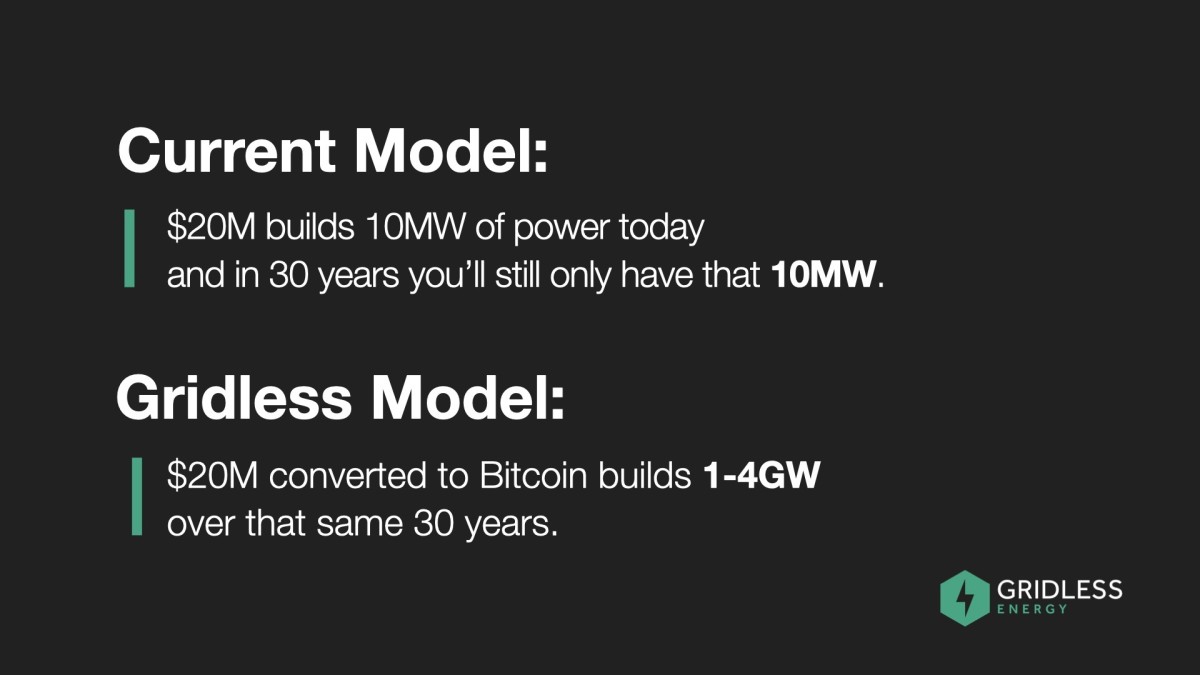

Thus, the private sector has commenced establishing mini-grids. Private enterprises have exerted their best efforts with these mini-grids. However, they require substantial capital, leading to challenges in securing funding. Even once established, the consumers around the area might not possess significant wealth. They might be considering, “Should I prioritize electricity or food?”

The firms that create the mini-grids construct power facilities that harness hydro energy. Suppose they aim to create one that generates one megawatt of power, but the community only utilizes 200 kilowatts. There exists 800 kilowatts generated from the river, yet for that 800 kilowatts, they receive nothing — zero shillings, zero dollars, nothing at all.

At Gridless, we propose, “That surplus electricity you’re unable to supply to anyone, is precisely what we seek.” This is referred to as stranded power or wasted energy, and it’s what we desire. Therefore, we step in as your last resort buyer.

We create an agreement to utilize that surplus electricity, and from a revenue-sharing perspective, we collaborate. It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement. Our data centers harness that electricity to mine bitcoin.

Then, the electrification catalyzes further development. By utilizing that electricity, it becomes a revenue source for the power generation facility. They were earning no profit from that electricity before, and now they’re benefiting from it.

What have we observed as a result? First, they can broaden their reach, distributing electricity further. Additionally, some of them have managed to reduce their prices. Consequently, consumers within reach who previously refrained from using electricity due to cost are now saying, “Hey, connect me. I can afford to pay for this now.”

Corva: So, in a way, you’re subsidizing the cost of electricity.

Maingi: Yes, because we step in and utilize this energy, the energy provider can offer better pricing and expand its reach. So, what does this entail? More homes receiving electricity, more small businesses gaining power, more factories getting energized, and more health facilities obtaining electricity. You can envision the positive feedback loop that emerges.

Nevertheless, the challenge lies in doing business in Africa being akin to an extreme sport.

Corva: Why is that?

Maingi: To start, consider merely acquiring the equipment. The mining devices are sourced from China, either from Bitmain or MicroBT, or from a company in the U.S., and the process of importing them to Africa can be quite arduous.

We received a shipment from the U.S. that took over 60 days just to clear into the country. This timeline stretched from placing them on a vessel to their arrival here. It doesn’t account for coordinating the logistics of getting the miners on-site and undergoing pre-shipment inspections to ensure they comply with Kenyan regulations.

The entire process can extend to almost 120 days from start to finish. If you’re operating a business, waiting 120 days for your product to arrive is excruciating.

Furthermore, these machines are optimized for use in China or the U.S.

However, operational conditions in Africa differ significantly.

Corva: Does this relate to air quality?

Maingi: Absolutely. Air quality, dust, heat — in Kenya, average temperatures fluctuate between 20 to 40 degrees Celsius. When you run those machines in an environment with an average temperature around 30 degrees Celsius, the heat they must manage becomes evident.

Additionally, there’s dust. When you receive a pre-fabricated shipping container from China or elsewhere, you’ll find that the designers primarily focus on air inflow and outflow. However, we’ve identified problems with dust, necessitating the installation of dust filters on the machines.

Moreover, in 2022, we discovered when we established our first site that the lights on the miners attracted insects. During the rainy season, the bugs were drawn to the lights, flying into the fans and getting crushed — an oversight that hadn’t been considered.

Initially, the shipping containers were projected to cost us $100,000 each, which was unsustainable for profitability. The figures simply didn’t add up. Consequently, we devised our own container.

Corva: Remarkable.

Maingi: Right? That’s what we’ve been implementing at a quarter of the previous cost. Additionally, the advantage of being produced in Kenya has enabled us to traverse the COMESA (Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa) region without incurring extra duties.or tariffs because it’s acknowledged as a COMESA product.

This also assisted as, being produced in Kenya, it’s quite straightforward for us to transport the containers across the COMESA area without incurring additional taxes. We receive a tax exemption. Even if the containers from China were advantageous, if we brought them to Kenya and needed to relocate them to Uganda, I would also be liable for taxes in Uganda.

For every country you transport foreign products to, you must again pay taxes. Thus, it has been challenging, but positive solutions have emerged from these obstacles.

Have you heard of GAMA, the Green Africa Mining Alliance?

Corva: Yes.

Maingi: During the inaugural Africa Bitcoin Mining Summit last year, we unveiled a blueprint for the container we crafted. Anyone interested in using it to construct their own container based on our blueprint is welcome to do so.

Where you require our assistance, we will be prepared to guide you. That’s the essence of GAMA — How do we leverage our mutual strengths? How can we benefit each other? How do we find a young woman aiming to commence mining and support her throughout the journey of getting started?

Corva: Remarkable. I wish to revisit the topic of electrification in Africa. You mentioned earlier that you wanted to share some statistics.

Maingi: What I intended to convey is that there’s a ripple effect when we collaborate with the energy producer. We’ve been able to observe more households receiving connections.

If you’ve been in rural Kenya or Africa, you grasp how a single bulb can transform a life. For instance, consider children returning home from school. They have assignments and rely on these small paraffin lamps to study. The fumes from them are detrimental to their health. However, this is a child with no backup plan. The teacher anticipates this child to return with her assignments completed. Lacking electricity is not an acceptable excuse.

Once a man shared with me that sometimes, while his daughter is engrossed in her assignment, the paraffin runs out. With the nearest gas station nearly four miles away, who is going to venture out to look for paraffin at that hour? No one. Tough luck.

Thus, the child arrives at school either in trouble for failing to complete her assignments or falling behind because now those so-called “are your personal issues.” Due to that one bulb they now possess, he said, “My daughter is excelling in school.” Moreover, in terms of health, all those hospital visits they had to make because she was inhaling the paraffin fumes have significantly decreased.

Corva: It seems you want to make me emotional.

Maingi: No, there’s no need for tears. (Author’s note: This woman is serious.) It’s a fact.

Moreover, in Zambia, I recall conversing with women discussing childhood vaccinations. Between the ages of zero and three years, there are specific vaccinations recommended by the WHO that your child must receive — measles, polio, etc. — but the nearest health center providing them sometimes isn’t readily accessible.

Hence, you do your calculations, and you conclude, “I cannot afford bus fare for this.” Thus, if a disease sounds more severe, you think, I’ll get my child vaccinated for that one, while this one I’ll neglect. However, in reality, all of them are crucial for children.

Now, Gridless is entering Malawi and enabling electricity providers to connect additional households in the Bondo region. Health centers are being energized, so more vaccinations are available at more local clinics.

Previously, you might have said “Polio seems serious, I’ll get my child that vaccine, but with measles, I don’t know anyone who has died of that lately, so perhaps I won’t vaccinate my child for that one,” but now more individuals can access it.

Now, we will cultivate a young generation who, we believe, as we continue these efforts, is going to prosper. They will develop. Additionally, we might significantly reduce childhood mortality rates because these rural areas receive electrification.

Corva: And supplying energy to these regions also aids in sustaining livelihoods, I presume.

Maingi: Absolutely. There’s a tea factory in Muranga, Kenya, located in the highlands.

We collaborated with the energy generator in the region, and they managed to supply power to the factory. Now, their facilities can support the tea factory, which has two advantages: tea farmers can deliver their tea to the factory, meaning it won’t spoil on the farms due to delayed transportation, and increased employment has also emerged simply from the tea factory becoming an energized space.

We continually assert that our knowledge of this will induce change is rooted in the fact that energy is foundational to human advancement.

Corva: There’s no such thing as an energy-deprived nation that’s wealthy.

Maingi: If you examine Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, it previously prioritized food, shelter, clothing, but I place energy there. Energy is a fundamental necessity. It’s indispensable for anyone to genuinely lead a respectable life. For individuals to earn a decent living, energy must be part of that equation.

Corva: Is it accurate that you’ve recently developed software that aids in energy demand response?

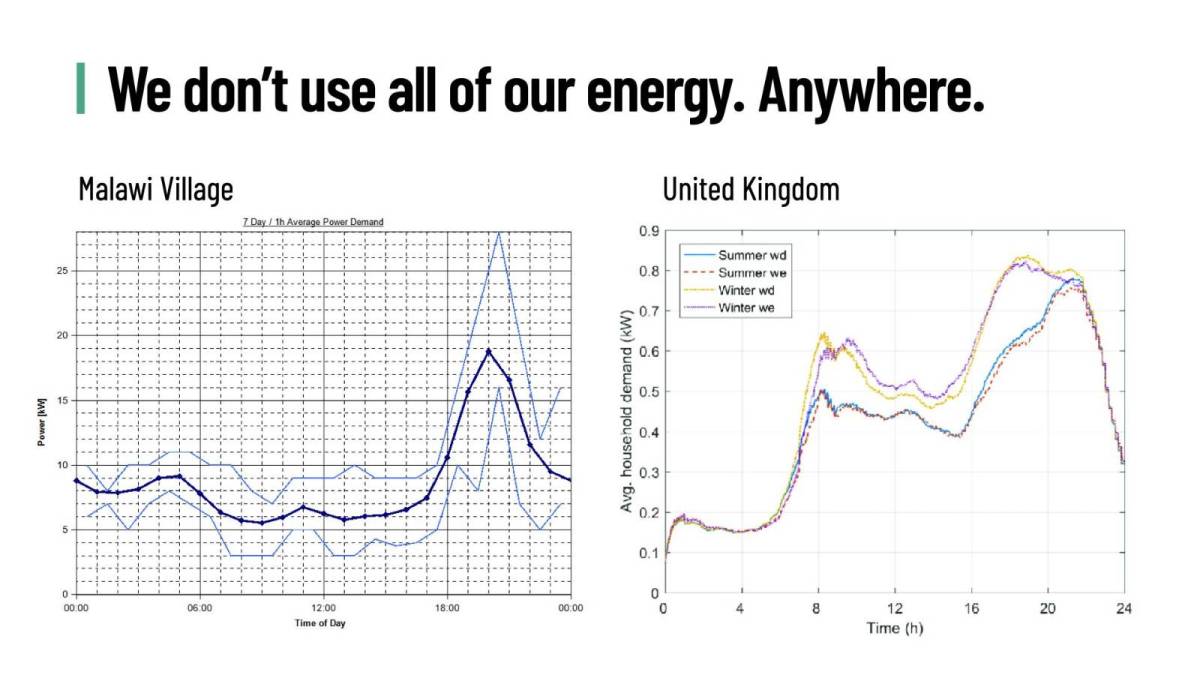

Maingi: Yes. We recognized that we must be more proactive in establishing real-time demand response. Previously, we were either reacting too late or too early to the power available.

Keep in mind we are the last resort buyers, so communities take precedence, followed by small enterprises. To uphold that pledge, we had to ensure we weren’t consuming electricity that someone else required at that moment.

So, let me illustrate. In typical households, individuals awaken at 6 a.m., initiating a surge in electricity. At that moment, our software receives a signal and reduces our consumption to align with the grid’s needs. Then, at 8 a.m., everyone heads to school and switches off their lights, leading to excess electricity in the grid. That is when we power more mining machines.

We receive the signal, power additional machines, absorb the electricity, and continue until around 6 p.m. when people return home and require the electricity. Gridless reduces the power to their machines and returns the electricity.

At 10 p.m., everyone goes to sleep, and we activate more machines. This entire process is facilitated by software we developed internally called Gridless OS. It enables real-time demand response. It ensures that everyone obtains what they require, stabilizing the grid.

Corva: Are you establishing certain benchmarks with Gridless that others are emulating in Africa or other global regions?

Maingi: It has set a precedent that others are adopting. Occasionally, you attend conferences, and people continually reference Gridless. That’s when you realize, “My goodness, this concept has grown beyond our expectations.” Thus, you start to appreciate how this has impacted change, underscoring that it does not exist in isolation.

Ultimately, individuals have distinct methods of mining bitcoin, and there’s a positive effect on the community regardless of the approach taken. Look at Bigblock Datacenter — Sebastian Gouspillou in the Congo — where they’re utilizing the heat to dry cocoa for chocolate they produce. Consider the economic benefits created by that.

Corva: I believe Sebastian made me emotional as well when I met him.

Maingi: What excites us and other stakeholders in this field is that we are the ones who comprehend our challenges, and it’s thrilling to see African companies deciding “Not only will I mine bitcoin profitably and decentralize the network, but there will also be some advantage to our community, as well.”