Assessing decentralization in blockchain

Decentralization refers to the distribution of control and decision-making throughout a network rather than being concentrated in a singular authority.

In contrast to centralized systems, where one organization oversees everything, decentralized blockchains share data among participants (nodes). Each node maintains a copy of the ledger, promoting transparency and minimizing the chance of manipulation or systemic failure.

Within blockchain, a decentralized structure yields notable benefits:

- Security: Decentralization diminishes vulnerabilities tied to central attack points. In the absence of a singular controlling body, it becomes more difficult for malicious entities to breach the network.

- Transparency: Every transaction gets documented on a public ledger that all participants can access, enhancing trust through openness. This transparency guarantees that no solitary entity can alter data without widespread agreement.

- Fault tolerance: Decentralized infrastructures are more robust against failures. The distribution of data across various nodes ensures that the system continues to function even if some nodes experience issues.

Therefore, while decentralization is advantageous, it’s not a permanent state. It operates on a continuum, consistently evolving with network engagement, governance frameworks, and consensus protocols.

And indeed, there is a standard for measuring it. It’s referred to as the Nakamoto coefficient.

What does the Nakamoto coefficient signify?

The Nakamoto coefficient is a measurement utilized to gauge the decentralization of a blockchain network. It indicates the minimum number of independent actors — including validators, miners, or node operators — that would need to cooperate to disrupt or undermine the network’s regular functioning.

This idea was first presented in 2017 by former Coinbase CTO Balaji Srinivasan and is named after the creator of Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto.

A higher Nakamoto coefficient reflects enhanced decentralization and security within the blockchain network. In such systems, control is more broadly distributed among participants, making it increasingly challenging for any small group to manipulate or assault the network. Conversely, a reduced Nakamoto coefficient suggests that fewer entities possess substantial command, increasing the likelihood of centralization and potential risks.

For instance, a blockchain with a Nakamoto coefficient of 1 would be highly centralized, as a single entity could dictate the network’s operations. Alternatively, a network with a coefficient of 10 would necessitate at least 10 independent actors to conspire to exert influence, indicating a more decentralized and secure framework.

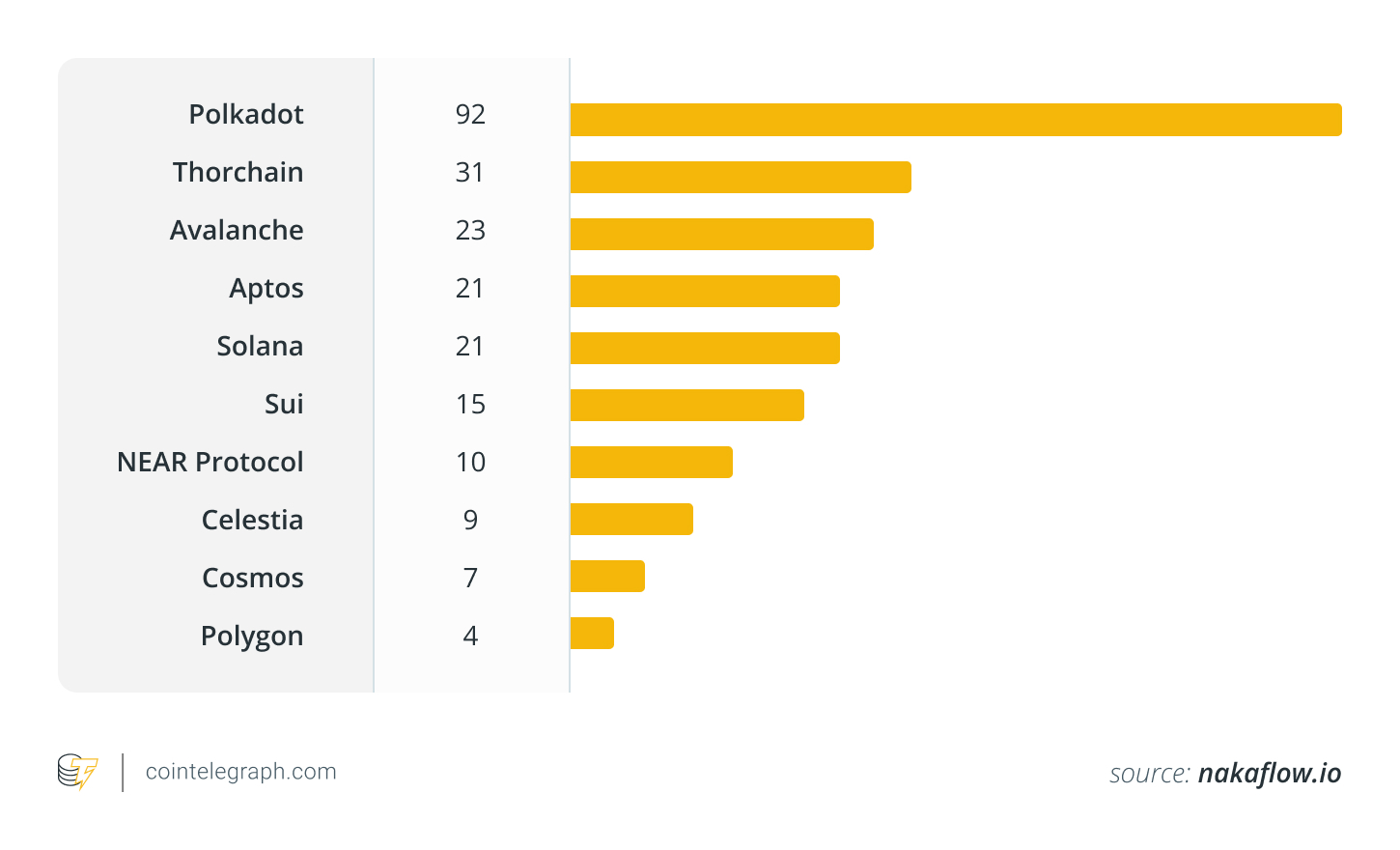

Did you know? Polkadot’s impressive score on the Nakamoto coefficient primarily stems from its nominated proof-of-stake (NPoS) consensus mechanism, which encourages an equitable distribution of stakes among a vast array of validators.

Determining the Nakamoto coefficient

Determining this coefficient encompasses several essential steps:

- Identifying key entities: Firstly, ascertain the primary players within the network, such as mining pools, validators, node operators, or stakeholders. These parties are vital in sustaining the network’s operations and security.

- Evaluating the control of each entity: Then, appraise the degree of control each identified actor holds over the network’s resources. For example, in proof-of-work (PoW) blockchains such as Bitcoin, this requires examining the hashrate distribution among mining pools. In proof-of-stake (PoS) systems, it involves analyzing the stake distribution among validators.

- Summation to identify the 51% threshold: After evaluating individual controls, rank the entities from highest to lowest based on their influence. Then, cumulatively sum their control percentages until the total surpasses 51%. The number of entities necessary to achieve this threshold is the Nakamoto coefficient.

Consider a PoW blockchain with the following distribution among mining pools:

- Mining pool A: 25% (of the total hashrate)

- Mining pool B: 20%

- Mining pool C: 15%

- Mining pool D: 10%

- Others: 30%

To calculate the Nakamoto coefficient:

- Begin with mining pool A (25%).

- Add mining pool B (25% + 20% = 45%).

- Add mining pool C (45% + 15% = 60%).

In this case, the aggregate hashrate of mining pools A, B, and C reaches 60%, exceeding the 51% threshold. Hence, the Nakamoto coefficient is 3, indicating that cooperation among these three entities could jeopardize the network’s integrity.

Did you know? Despite Bitcoin’s standing as a decentralized platform, its mining infrastructure is considerably centered. The current Nakamoto coefficient for Bitcoin is 2, implying that just two mining pools dominate most of its mining capabilities.

Constraints of the Nakamoto coefficient

While the Nakamoto coefficient is a significant metric for evaluating blockchain decentralization, it presents certain limitations that necessitate thoughtful consideration.

For instance:

Static representation

The Nakamoto coefficient offers a fixed snapshot of decentralization, mirroring the minimum number of entities necessary to threaten a network at a particular moment.

However, blockchain networks are fluid, with participant roles and power shifting due to factors such as staking, mining power changes, or node participation variations. As a result, the coefficient might not accurately reflect these temporal changes, potentially resulting in outdated or misleading evaluations.

Subsystem emphasis

This indicator generally emphasizes specific subsystems, such as validators or mining pools, which may neglect other vital elements of decentralization. Considerations like client software diversity, geographical spread of nodes, and concentration of token ownership also significantly influence a network’s decentralization and security.

Relying exclusively on the Nakamoto coefficient could lead to an incomplete assessment.

Diversity of consensus mechanisms

Various blockchain networks utilize distinct consensus methods, each affecting decentralization in unique ways. The Nakamoto coefficient may not apply uniformly across these varied systems, necessitating customized strategies for precise measurement.

External factors

External variables, such as regulatory measures, technological progress, or market trends, may impact decentralization over time. For example, regulatory conditions in certain regions can affect the functioning of nodes or mining operations, thereby reshaping the decentralization environment of the network.

The Nakamoto coefficient may not factor in such external changes, restricting its comprehensiveness.

In conclusion, the Nakamoto coefficient is a valuable tool for evaluating specific dimensions of blockchain decentralization. It should be supplemented with other metrics and qualitative evaluations to obtain a holistic view of a network’s decentralization and security.